One of my earliest memories of childhood is hearing my family talk about the remarkable time that a white man treated me like a regular little girl, not a little black girl.

I was glad that I did not live in slavery times. But I knew that conditions of life for my family and me were in some ways not much better than during slavery.

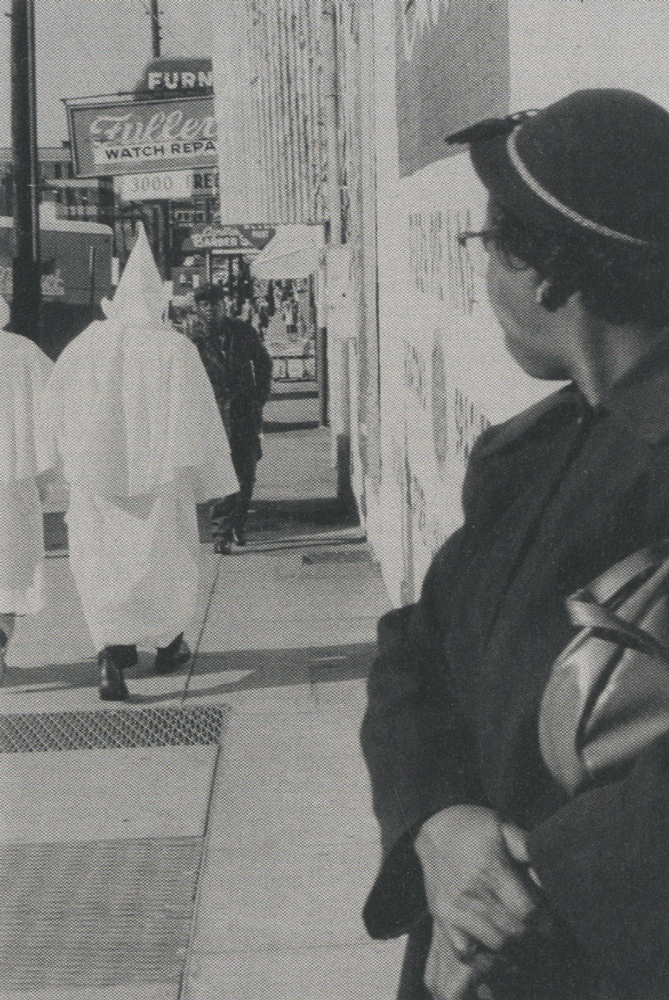

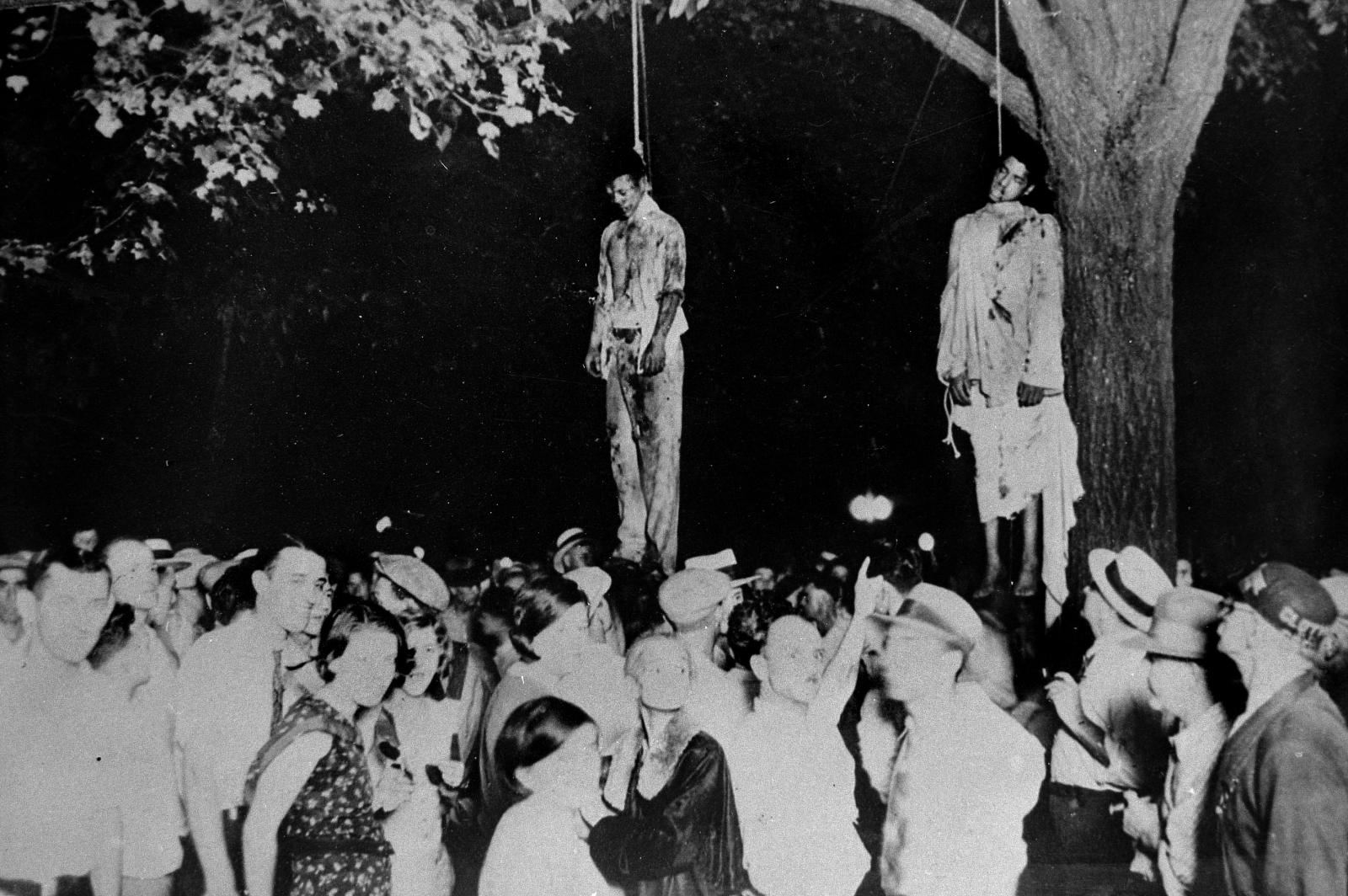

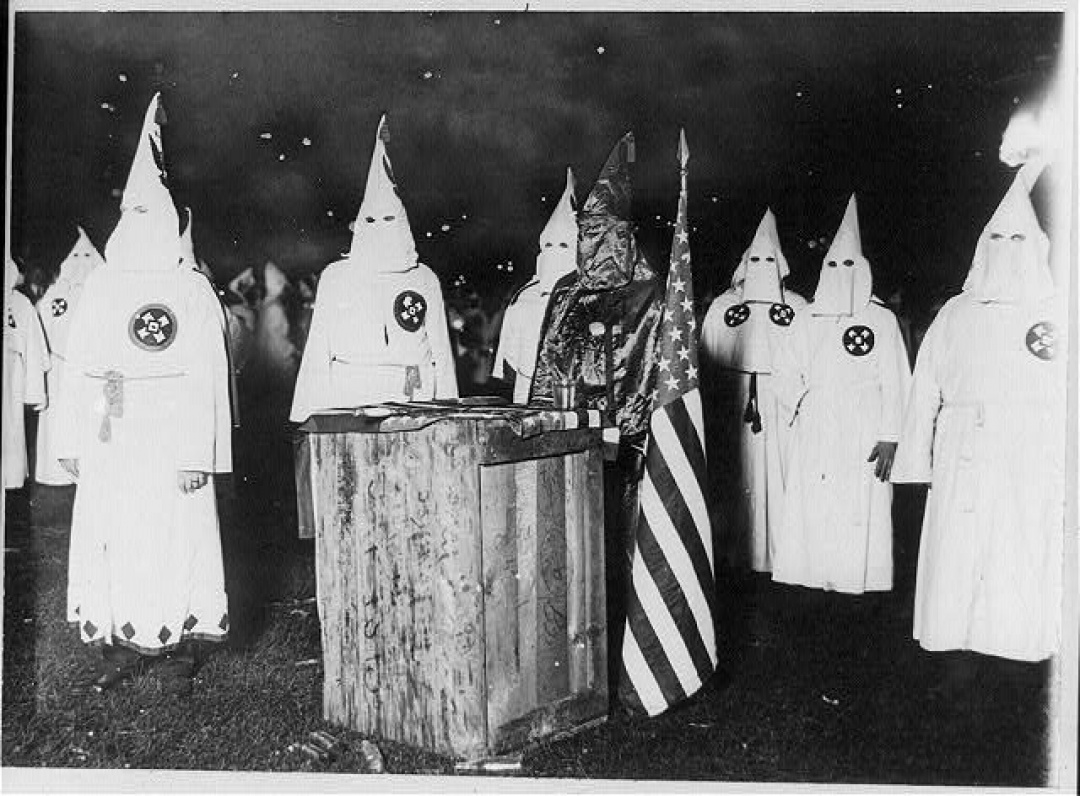

By the time I was six, I was old enough to realize that we were actually not free. The Ku Klux Klan was riding through the black community, burning churches, beating up people, killing people.

I do know that I had a very strong sense of what was fair. That attitude got me into trouble sometimes.

I remember when we walked to school, sometimes the bus carrying the white children would come by and the white children would throw trash out the windows at us.

“What would you all white folks do if you didn’t have us niggers to work for you?”[…]

“Sherman, if I didn’t have you all working for me, I’d have some others. I would have some more damn-fool niggers working.”

We never called him anything but Mr. Sherman or Mr. Gray, because he was an older man and we respected him. People used to call him the “top nigger.”

It was right after World War I, around 1919. I was five or six years old. Moses Hudson, the owner of the plantation next to our land in Pine Level, Alabama, came out from the city of Montgomery to visit and stopped by the house. Moses Hudson had his son-in-law with him, a soldier from the North. They stopped in to visit my family. We southerners called all northerners Yankees in those days. The Yankee soldier patted me on the head and said I was such a cute little girl. Later that evening my family talked about how the Yankee soldier had treated me like I was just another little girl, not a little black girl. In those days in the South white people didn’t treat little black children the same way as little white children. And old Mose Hudson was very uncomfortable about the way the Yankee soldier treated me. Grandfather said he saw old Mose Hudson’s face turn red as a coal of fire. Grandfather laughed and laughed.

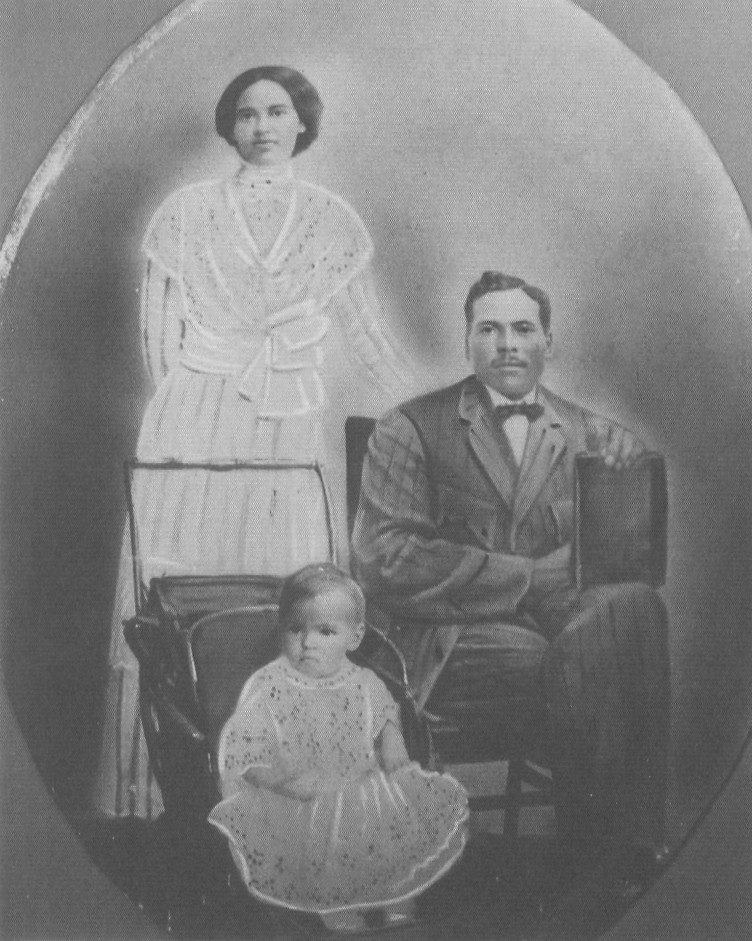

I was raised in my grandparents’ house in Pine Level, in Montgomery County, near Montgomery, Alabama. All my mother’s people came from Pine Level, My mother’s name was Leona Edwards. My father came from Abbeville, Alabama. His name was James McCauley. He was a carpenter and a builder, very skilled at brick- and stonemasonry. He traveled all around building houses.

My father’s brother-in-law, Reverend Dominick, Aunt Addies husband, was pastor of the Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church in Pine Level, and it was there in Pine Level that my father met my mother, who was a teacher. They were married right there in Pine Level on April 12, 1912. My mother was twenty-four years old, and my father was the same age.

After they were married, they moved to Tuskegee, Alabama, to live. It was the home of Tuskegee Institute, which Mr. Booker T. Washington had founded back in 1881 as a school for blacks. My parents lived not far from it. Both black and white leaders called the town of Tuskegee a model of good race relations, and that may have been why my father wanted to move there, And there were a lot of building jobs in the county of Macon, Alabama. My mother got a job teaching.

It wasn’t long before they started a family. I was born on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, and named Rosa after my maternal grandmother, Rose. My mother was around twenty-five years old by the time I was born, but she always said that she was unprepared to be a mother. I guess she was unhappy because my father worked on building homes in different places in the county and she was left alone quite a bit. She had to quit teaching until after I was born, and she always talked about how unhappy she was, being an expectant mother and not knowing many people. At that time women who were pregnant didn’t get out and move around and socialize like they do now. They stayed pretty much to themselves. She said she spent a lot of time crying and weeping and wondering what she was going to do and how she was going to get along, because she wasn’t used to having a child to take care of.

I came along and I was a sickly child, small for my age. It was probably hard for my mother to take care of me. And my father’s younger brother came to live with us, so that was someone else to cook and wash for. My uncle Robert was a carpenter too, and he enrolled at Tuskegee Institute to take courses in carpentry and building. But my mother always said Uncle Robert knew so much about what they were trying to teach him that he was teaching the instructors. Every time they would say something about a building plan, he would say, “No, I think we should arrange to do it this way,” and then they would arrange it the way he suggested and it would come out right. He didn’t stay at Tuskegee Institute very long as a student.

I have pictures of the houses my father and my uncle built-beautiful houses. They learned from their father, I think. They didn’t learn anything at Tuskegee.

But Tuskegee was still the best place in Alabama for African Americans to get an education, and my mother wanted to stay there. Her idea was for my father to take a job at Tuskegee Institute. Teachers got houses to live in at that time, so they would have a place to stay. The other children they would have and I would get an opportunity for an education at the Institute. At that time black children in the South had very limited opportunities for schooling. But my father didn’t go along with that idea. He wanted to do contracting work and make more money. He and my mother didn’t agree on planning for the future.

My father decided he didn’t want to remain in Tuskegee. He wanted to go back to his family in Abbeville. My mother had no choice but to go with him.

So we went to Abbeville to live with my father’s family. It was a big family, with lots of children. My grandmother had started having children early and didn’t stop for a long time. When I was born, my father’s youngest brother, George Gaines McCauley, was eight years old. He used to tell me he was jealous of me because he’d been the baby for eight years and he didn’t like me as a new baby at all. But he liked me as I grew older.

I learned all I know about my father’s family from my young uncle George. He said that my father’s grandfather was unknown and someone said he was one of the Yankee soldiers who served in the South during the Civil War. My father’s grandmother was a slave girl and part Indian or something. That’s all I know. If my mother knew more than that, she never told me. I guess she felt she wasn’t as compatible with that family as she should have been with her in-laws.

I think my mother may have done some teaching in Abbeville, but she didn’t stay there long. My father decided to go north, and my mother didn’t want to stay with his family while he was gone. She was pregnant with my brother by then, and she decided to go back to live with her own parents, who had a small farm in Pine Level. They were all alone by then. The niece that they had been raising had married and left. My mother said she thought about the house in Abbeville with a father and mother and growing children, and then she thought about her own mother and father not having anybody with them. So she just up and left and went to stay with her parents.

My mother took me to live with her parents in Pine Level, Alabama, when I was a toddler. Later my father joined us, and we lived as a family until I was two and a half years old. He left Pine Level to find work, and I did not see him again until I was five years old and my brother was three. He stayed several days and left again. I did not see my father anymore until I was an adult and married.

My mother and father never got back together, They just couldn’t coordinate their lives together, because he wanted to travel and she wanted to be situated in a permanent home. My memories of my mother’s parents are very clear. In fact, my earliest memory is of my grandfather taking me to the doctor to look at my throat. I had chronic tonsillitis all through my childhood, but this was very early. I wasn’t more than about two and a half because it’s the only time I can remember being an only child in the house. My mother didn’t go. I think she was ailing-it must have been just before my brother was born. My grandfather took me to a store; there wasn’t a doctor’s office. Grandfather sat me up on the counter, and I remember I was wearing a little red velvet coat and bonnet. The doctor asked me to open my mouth, and I opened it, I can recall that everything the doctor asked me to do, I just obeyed very nicely. The people were amazed, with my being so small and being so little trouble. I opened my mouth, and he put something in it—I thought it was a spoon or something—to hold my tongue down. When Grandfather took me back home, he told my mother and grandmother about how well-behaved I was. That’s the first time I can remember anything at all about myself. I always liked to be praised about any little thing. I felt kind of happy because he thought I was such a good little girl.

Living in my grandparents’ house, I learned a lot more about my mother’s family history. My great grandfather, my grandmother’s father, had the last name of Percival. As a young Scotch-Irish boy he had been brought to the United States on a ship. He was white, but he wasn’t free.

In those days, over in Europe, poor white people were sometimes indentured servants. They signed an agreement that in return for their fare to America, they would work for someone for a particular number of years. During those years they had no rights and could be treated as poorly as slaves.

My great-grandfather arrived in this country through the port of Charleston, South Carolina, and then was brought down to Alabama. He was indentured to Some people named Wright in Pine Level, but they never changed his name from Percival, which I guess he brought with him from the old country, That was a difference between black slaves and white indentured servants. Black slaves were usually not allowed to keep their names, but were given new names by their owners.

He married Mary Jane Nobles, a person of African descent with no white ancestors. She was a slave and a midwife, who helped to deliver and care for babies. They were married and had three children, two daughters and a son, before freedom was declared by President Abraham Lincoln. Six other children were born free. Their oldest daughter Rose, my grandmother, was five years old when the Civil War ended with a Union victory over the Confederate states.

My grandmother told me that before the Union soldiers arrived, the slave owners had the slaves dig holes and bury many of the slave owners’ most valuable household possessions-dishes, silver, and jewelry. The younger slave children were then sent to sit and to play on the freshly dug soil to tamp it clown.

After the war ended, slavery was also ended. But many former slaves stayed where they were. They didn’t know where else to go and did not want to leave their homes. My great-grand parents stayed on in their small log house on the Wrights’ land and continued to work for the family. Lite was not very different from before, but they knew they were free to leave if they wanted to. They also had the right to purchase land. I don’t know how or when they did it, but some time after Emancipation my great grandparents purchased twelve acres of land that had been part of the Hudson plantation.

After slavery was ended and the folks found out they were free, that’s when my great-grandfather built a little table so his family would have something to eat on. My grandmother was six years old at the time, and the oldest child, and she helped him by holding up a burning pine knot so he could see to work at night. I still use that table today. During the day my great-grandfather made furniture for MI. Wright, his former master. I suppose he was using MI. Wright’s tools when he made that little table, or maybe even his own hammer and gimlet. A gimlet is a little tool you use to bore holes in wood. Instead of using nails, he would sharpen a little piece of wood down kind of small and put it in there as a peg. That’s how he put the table together.

After Emancipation, my grandmother moved into the house with the Wright family to take care of their child. She wasn’t much older than six, but she was large enough to take care of a small child. She didn’t have to go out in the fields to work and did not have much work to do around the house either.

My grandfather’s father was a white plantation owner named John Edwards, and his mother was a slave housekeeper and seamstress who never went out to work in the fields. I guess she was probably of mixed black and white blood, because my grandfather, the child she had with her owner, was so close to white. She died when my grandfather was very young, and then John Edwards, the plantation owner, died too.

After that, their child, my grandfather Sylvester, was treated very badly. An overseer named Battle took over the plantation, and he disliked my grandfather so much that he beat him every time he saw him. I used to hear my grandfather say that when he was small, the only food he remembered getting was the scraps the kitchen workers would slip to him. The overseer beat him, tried to starve him, wouldn’t let him have any shoes, treated him so badly that he had a very intense, passionate hatred for white people. My grandfather was the one who instilled in my mother and her sisters, and in their children, that you don’t put up with bad treatment from anybody. It was passed down almost in our genes.

I remember that he was very emotional and excitable. My grandmother was the calm one. My grandfather was very light complected, with straight hair, and sometimes people took him for white. He took every bit of advantage of being white-looking. He was always doing or saying something that would embarrass or agitate the white people. With those who didn’t know him, when he was talking with them he would extend his hand and shake hands with them. He’d be introduced to some white man he didn’t know, and he’d say, “Edwards is my name,” and shake hands. Then people who knew him would get embarrassed and have to whisper to the others that he was not white. At that time no white man would shake hands with a black man. And black men weren’t supposed to introduce themselves by their last names, but only by their first names.

And I remember that sometimes he would call white men by their first names, or their whole names, and not say “Mister.” The whites wouldn’t always like that too well; in fact, he was taking a big risk. At that time black people were never supposed to call a white person by name without saying “Mister” or “Miss.”

My grandfather had a somewhat belligerent attitude toward whites in general. And he liked to laugh at whites behind their backs. My grandfather did not want my brother and me to play with white children. The white overseer of the Hudson plantation had some children just about my age and my brother’s age. When we wanted to play with them, or when they wanted to play with us, Grandfather would be very hostile. He made us stay away from them. We wouldn’t even have to be close to them. We might be sitting on the ground under the shade of the wagon, playing, and he would yell at us and have us leave from around them.

Any little thing he could do, he did. It wouldn’t be anything of great significance, but it was his small way of expressing his hostility toward whites. The whites never did anything to him because of his attitude. How he survived doing all those kinds of things and being so outspoken, talking that big talk, I don’t know, unless it was because he was so white and so close to being one of them. I guess they knew him well enough to not bother him physically about it.

His irritability also might have had something to do with his being crippled. He had arthritis. We called it rheumatism then. I don’t know how old he was when he became crippled, but I think he was very young. He could hardly wear shoes without cutting holes in the toes, and sometimes he couldn’t walk at all. And there he was, trying to take care of a family.

He and my grandmother married very young, and the one thing he wanted most of all was for none of his children or anyone related to him to ever have to cook or clean for whites. He wanted all his children to be educated so they wouldn’t have to do that kind of work.

Domestic work paid very little, and those who did domestic work were not respected. Most domestic workers worked very hard and did not have an opportunity to be educated. That’s why my grandfather wanted my mother to become educated and teach school. Teaching was a prestigious job, and it paid more. African-American teachers did not receive as much pay as Caucasian teachers, but they were paid more than domestic workers.

My grandfather and grandmother had three daughters. There was one daughter who died in her teens. She never went away from home to school. Another daughter, Fannie, did just what my grandfather didn’t want: She left home and went to work in the city of Montgomery in white people’s homes. She never went away to school, so that me and she never got past the sixth grade, because the black schools around Pine Level didn’t go past the sixth grade. For high school you had to go away. She was about seven years older than Illy mother. Either my grandfather didn’t have enough money to send both her and my mother to school or the older one didn’t want to go. Most southern women, black or white, didn’t go beyond grammar school in those days. I think at one time I heard my mother say that my grandfather had hopes of his oldest daughter being educated, but I guess Fannie had a different idea. Maybe she wanted to make some money right away, even though it was Just the little bit of money that housekeepers could make at that time. I think she wanted to be on her own and she was until she got married. She married before my mother did by several years.

My mother, Leona Edwards, went to school in Selma, Alabama, at Payne University. She didn’t go long enough to get a bachelor’s degree, but she did get a teaching certificate. She taught in Pine Level, and then of course she met my father and they got married.

After my mother took me back to Pine Level to live with my grandparents, and after my brother, Sylvester, was born, she went back to teaching. The Pine Level black school already had a teacher, so she had to go and teach in the village of Spring Hill. It was too far away for her to walk back and forth every day and still prepare her lessons, so during the week she stayed with a family there, I can remember when she left in the wagon with my grandfather driving. He used a little mule wagon to travel around in. I wasn’t exactly sure why she was going away. I said to my grandmother, “Is Mama Leona going to learn how to teach school?” My grandmother said, “No, she’s been teaching school since before you were born, so she’s just going to teach school.” We got that straight, but I was very glad when my mother came back.

I liked being with my grandparents. Sometimes they would take me fishing at a creek on the plantation. Being a little bit up in age, sometimes they couldnt get the bait on the hook, so I used to bait the hooks for them. I guess that’s why they liked to take me fishing. I’d get the worm and he could wiggle all he wanted to. All I had to do was get one end of him started on the hook. Some people used to hit the worms and kill them, but I always believed that the fish should see that worm moving on the hook and that they’d bite a lively worm much sooner than a dead one. People used to use other things besides worms too, like fat meat and crawfish rails.

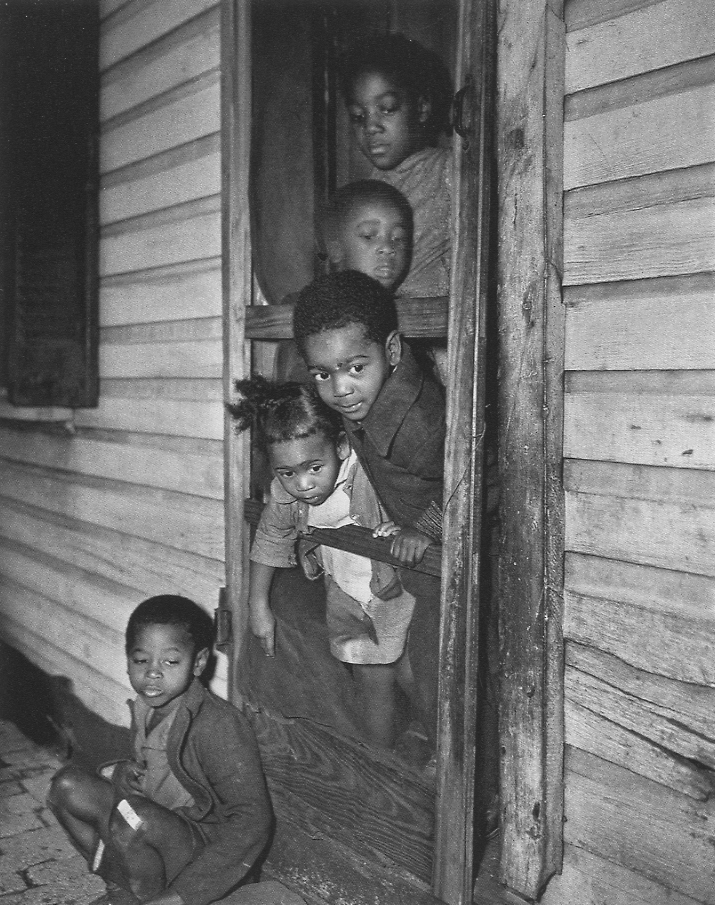

Sylvester, who was named for my mother’s father, was two years and seven months younger than me. He followed me around all the time. Whatever I said, he would say it too. He was always getting into mischief, but I was very protective of him. I don’t remember this myself, but my grandmother told me that one time when my mother was away, she was going to give my brother a whipping. He was just a little fellow, and she was scolding him, and then she took up a little switch. I said, “Grandma, don’t whip brother. He’s just a little baby and he doesn’t have no mama and no papa either.” And so, she said, she put the switch down and looked at me and decided she would not whip him that day. I can remember what a mischievous little boy he was and how I got more whippings for not telling on things he did than I did for things I did myself. I never did get out of that attitude of trying to be protective of him.

Maybe the habit of protecting my little brother helped me learn to protect myself. I do know that I had a very strong sense of what was fair. That attitude got me into trouble sometimes.

One day when I was about ten, I met a little white boy named Franklin on the road. He was about my size, maybe a little bit larger. He said something to me, and he threatened to hit me—balled his fist up as if to give me a sock. I picked up a brick and dared him to hit me. He thought better of the idea and went away.

I didn’t think any more of it, and I guess neither did he. But I just happened to mention to my grandmother one morning, “I saw Franklin. He threatened to hit me, and I picked up a brick to hit him.” She scolded me very severely about how I had to learn that white folks were white folks and that you just didn’t talk to white folks or act that way around white people. You didn’t retaliate if they did something to you.

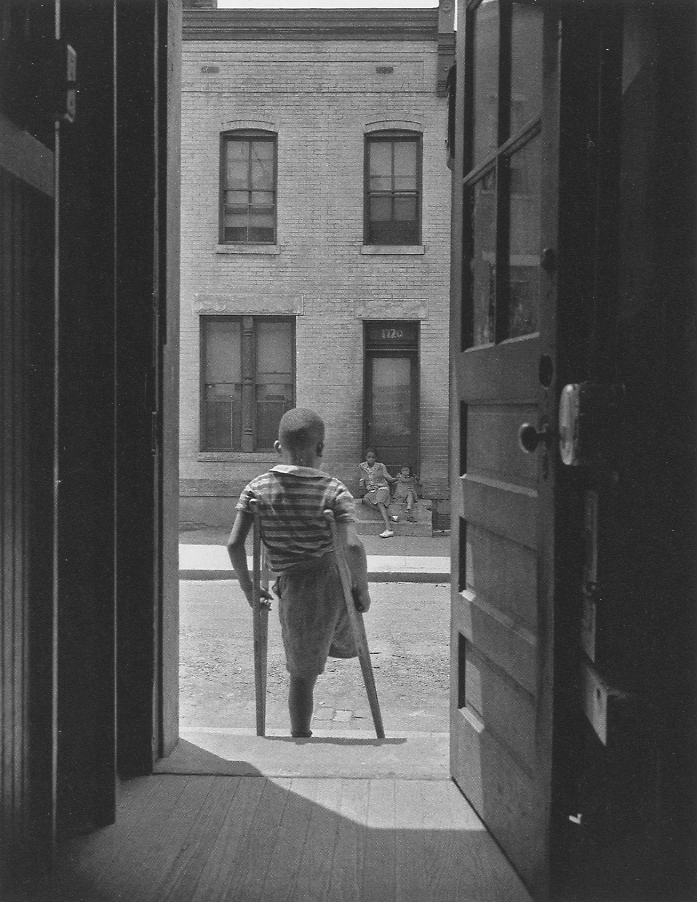

I liked Miss Beulah, and I liked school. We had fun there. At recess the girls would play what we called “ring gaines,” like Little Sally Walker Sitting in the Saucer, Rise Sally Rise, and Ring Around the Roses. The boys would play ball. I don’t think the girls played much ball at school. We used to play at home a little bit. My mother would buy us a ball, and we’d have to be very careful because pretty soon a rubber ball would be lost. It didn’t last too long. We called what we played baseball. I wasn’t too active in it, because if I tried to be active I’d fall down and get hurt. I wasn’t very good when it came to running sports.

Some of the older boys at school were very good at running sports and playing ball. They were also the ones who were responsible for wood at the school. The larger boys would go out and cut the wood and bring it in. Sometimes a parent would load a wagon up with some wood and bring it to the school, and the boys would unload the wagon and bring the wood inside.

They didn’t have to do this at the white school. The town or county took care of heating at the white school. I remember that when I was very young they built a new school for the white children not very far from where we lived, and of course we had to pass by it. It was a nice brick building, and it still stands there today. I found out later that it was built with public money, including taxes paid by both whites and blacks. Black people had to build and heat their own schools without the help of the town or county or state.

Another difference between our school and the white school was that we went for only five months while they went for nine months. Many of the black children were needed by their families to plow and plant in the spring and harvest in the fall. Their families were sharecroppers, like my grandparents’ neighbors. Sharecroppers worked land owned by plantation owners, and they got to keep a portion of the crop they grew. The rest they had to give to the owner of the plantation. So they needed their children to help. At the time I started school, we went only from late fall to early spring.

I was aware of the big difference between blacks and whites by the time I started school. I had heard my grandfather’s stories about how badly he was treated by the white overseer when he was a boy. My mother told me stories the old people had told her about slavery times. I remember she told me that the slaves had to fool the white people into thinking that they were happy. The white people would get angry if the slaves acted unhappy. They would also treat the slaves better if they thought the slaves liked white people.

When white people died, their slaves would have to pretend to be very sorry. The slaves would spit on their fingers and use it to wet their cheeks like it was tears. They’d do this right in front of the little slave children, and then the children would do the same thing in the presence of the grieving white people.

I was glad that I did not live in slavery times. But I knew that conditions of life for my family and me were in some ways not much better than during slavery.

I realized that we went to a different school than the white children and that the school we went to was not as good as theirs, Ours didn’t have any glass windows, but instead we had little wooden shutters. Their windows had glass panes.

Some of the white children rode a bus to school. There were no school buses far black children. I remember when we walked to school, sometimes the bus carrying the white children would come by and the white children would throw trash out the windows at us. After a while when we would see the white school bus coming, we would just get off the road and walk in the fields a little bit distant from the road. We didn’t have any of what they call “civil rights” back then, so there was no way to protest and nobody to protest to. It was just a matter of survival-like getting off the road-so we could exist from day to day.

Pine Level was too small to have the kind of segregation they had in the cities. I don’t know what the ratio of blacks to whites was, but it was a small town. There were very few public facilities, like buses and water fountains, so as a child growing up in Pine Level, I didn’t see any drinking fountains marked “Colored” and “White.” There was no “downtown.” There were just three stores; all basically general stores. All the merchants were white. There was a post office in one of the stores. There was no railroad depot there, and there wasn’t any train nearer than about twelve miles, in a place called Ramer, which was farther west.

By the time I was six, I was old enough to realize that we were actually not free. The Ku Klux Klan was riding through the black community, burning churches, beating up people, killing people. At the time I didn’t realize why there was so much Klan activity, but later I learned that it was because African-American soldiers were returning from World War I and acting as if they deserved equal rights because they had served their country.

The whites didn’t like blacks having that kind of attitude, so they started doing all kinds of violent things to black people to remind them that they didn’t have any rights.

At one point the violence was so bad that my grandfather kept his gun—a double-barreled shotgun—close by at all times. And I remember we talked about how just in case the Klansmen broke into our house, we should go to bed with our clothes on so we would be ready to run if we had to. I can remember my grandfather saying, “I don’t know how long I would last if they came breaking in here, but I’m getting the first one who comes through the door.”

We lived right on what they called a highway, which was gravel and not paved at that time. The Klansmen rode on that highway. My grandfather wasn’t going outside looking for any trouble, but he was going to defend his home. I remember thinking that whatever happened, I wanted to see it. I wanted to see him shoot that gun. I wasn’t going to be caught asleep. I remember that at night he would sit by the fire in his rocking chair and I would sit on the floor right by his chair, and he would have his gun right by just in case.

We were fortunate that the Klansmen never did try to break into our house, and after a while that particular period of violence ended. But there was always violence, and you’d hear about it every time.

I was young and hadn’t done much reading about racism, but I did a lot of listening. I heard a lot about black people being found dead and nobody knew what happened. Other people would just pick them up and bury them. Sometimes I’m asked how I Iived with that kind of fear, but that was the only way I knew and Pine Level was the only place I knew.

My grandparents were the only black people on that plantation who owned land. They had eighteen acres. Twelve acres were inherited from my greatgrandfather James Percival, who purchased the land for himself and his wife, my great-grandmother Mary Jane, after Emancipation and built a small log cabin, The other six acres were given to their daughter, my grandma Rose, to live on as long as she lived. Grandma Rose had taken care of a little girl in the Wright Iamily, who owned the land. When that little girl grew up, she married a merchant from Montgomery named Moses Hudson. The plantation was hers, but after she got married it became known as the Hudson Place. Moses Hudson gave her the land and the house where the Wrights had lived. This is the house we lived in.

On our land we had fruit, pecan, and walnut trees. We maintained a garden and raised chickens and a few cows. We didn’t have to buy many things at the stores. My grandfather was the one who usually went to the stores, but sometimes my brother and I would ride in the wagon with him. He would have eggs for sale, and he would trade the eggs for whatever else the family needed but didn’t have. He also sold chickens and calves. The stores had most everything we needed, including cloth. I don’t remember ever getting any ready-made gannents in Pine Level, but we could buy cloth and my mother would sew for us. The little money we earned was from my mother’s teaching and from working on other people’s land.

When we finished working on our own land, we used to work in Moses Hudson’s field. Mr. Sherman Gray was in charge of the field hands. We never called him anything but Mr. Sherman or Mr. Gray, because he was an older man and we respected him. People used to call him the “top nigger.” He was half white. He had a big family of children and they lived near us.

I was a field hand when I was quite young—not more than six or seven. I was given a flour sack like the other children and expected to collect one or two pounds of cotton. We would make it a game by seeing who could pick more. When I grew older and stronger, I picked cotton sometimes and chopped cotton at other times.

We picked cotton in the fall of the year after it had matured and was ready to go to the cotton gin. The gin separated the fiber from the cotton seeds. Chopping was done in the spring of the year, when the plants were young. You chopped the weeds from around the plant and sometimes also thinned out the cotton plants they would grow strong.

We were paid fifty cents per day for chopping cotton and one dollar per hundred pounds of picked cotton. I don’t know how much I could pick as a small child, because the children placed their cotton sacks on the ground in the same pile as the adults. Our family put all the cotton we picked together in one pile. When I was ten or twelve years old, my pile was weighed separately.

It was hard work picking and chopping cotton. We had a saying that we worked “from can to can’t,” which means working from when you can see (sunup) to when you can’t (sundown). I never will forget how the sun just burned into me. The hot sand burned our feet whether or not we had our old work shoes on.

Usually we didn’t wear shoes. There used to be an expression, “Didn’t nobody have shoes on but the hoss [horse] and the boss,” and that was how it was for us field hands on the Hudson Place. There were only two sets of good shoes in the field—on Mr. Freeman, the white overseer, and on the horse he rode through the field.

Mr. Freeman was in overall charge. It was his children my grandfather wouldn’t let Sylvester and me play with. Mr. Sherman Gray would go up to MI. Freeman and ask, “What would you all white folks do if you didn’t have us niggers to work for you?” suggesting that a compliment was in order for the high-quality work the field hands were doing. Mr. Freeman would answer in an authoritarian manner, “Sherman, if I didn’t have you all working for me, I’d have some others. I would have some more damn-fool niggers working.” That was exactly what he said. I know, because we were working right there in the field when he said it.

I remember thinking about that and also thinking about another man who was our neighbor. He had a big family of children too, and he was a completely unmixed black man—no white blood at all. He was an older man named Mr. Gus Vaughn. His wife and children worked in the fields, but Mr. Gus Vaughn didn’t do anything but walk around on his stick. He didn’t work for anybody. He didn’t do anything but walk around with his stick and talk big talk. Mr. Freeman couldn’t stand Mr. Gus Vaughn. He’d say, “Gus, I don’t like you.” Mr. Vaughn would answer, “There is no love lost,” and just keep walking. I didn’t understand what he meant at first, but later I found out that Mr. Gus Vaughn was saying he didn’t like Mr. Freeman either-there was no love lost between them.

So I saw that there was at least one black man who wouldn’t work for Mr. Freeman. And later on, when I heard white people say that it was the lightskinned black people who had the courage to stand up to whites, I’d always think back and remember Mr. Gus Vaughn who had no white blood.

Not all the white people in Pine Level were hostile to us black people, and I did not grow up feeling that all white people were hateful. When I was very young, I remember, there was an old, old white lady who used to take me fishing. She was real nice and treated us just like anybody else. She used to visit my grandparents a lot, and talk with them for a long time. So there were some good white people in Pine Level.