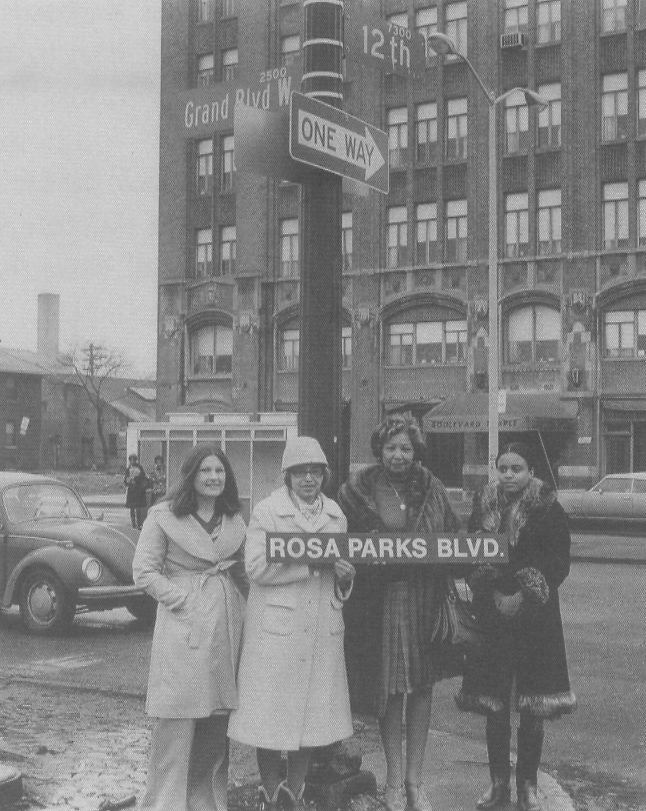

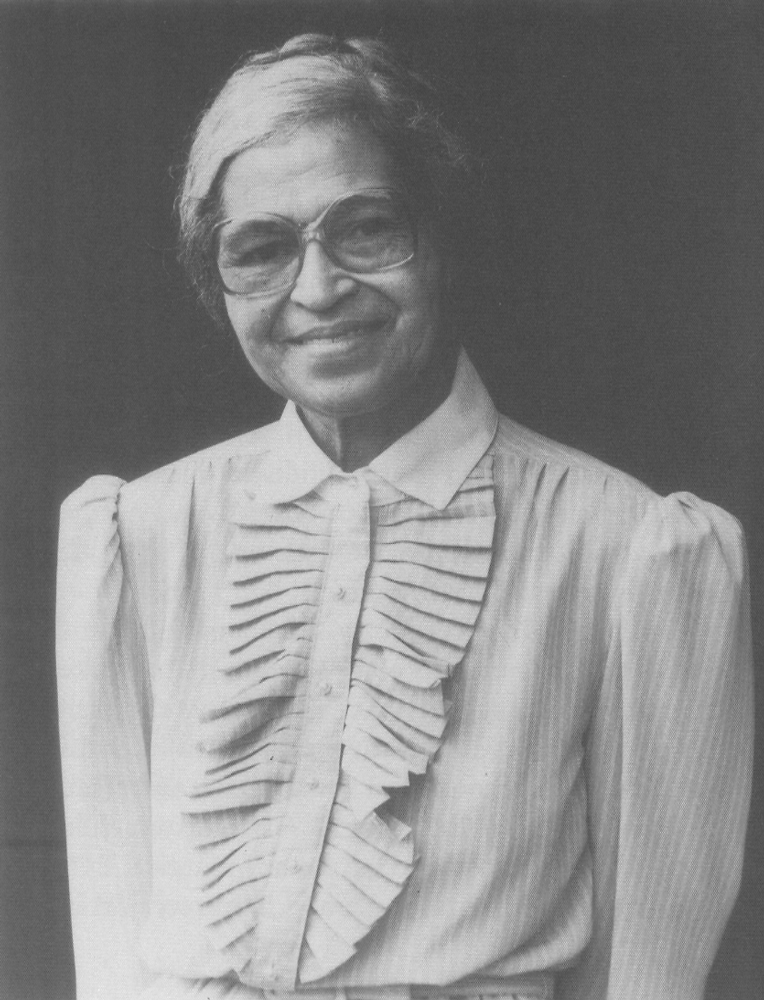

The Montgomery Bus Boycott’s place in history is secure. Rosa Parks became a national icon, famous worldwide as the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” Montgomery, Alabama, is known officially and unofficially as the “Birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement.”

But how accurate are these and similar labels? Just what were the Montgomery Bus Boycott’s contributions to the civil rights movement?

There is no denying that long before Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr. or even E.D. Nixon became household names, black citizens in the United States were fighting for their civil rights. The bus boycott that started in 1955 was far from the first attempt by black citizens to seek equal treatment in public transportation. Similar efforts included a boycott by blacks in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1953 to push bus drivers to obey the city’s ordinance permitting first-come, first-served bus seating.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 was not even the first boycott in Montgomery designed to oppose segregated transportation seating. A short-lived boycott—like the 1955 boycott, urged by black ministers—sprang up in 1900 to protest segregated seating on the city’s streetcar system. But it had no centralized organization and quickly dissipated.

Nor was the U.S. Supreme Court ruling enjoining Montgomery’s segregated bus seating the first or the most important civil rights decision by the court in the 1950s. That came in May 1954, when the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

Still, the Montgomery Bus Boycott deserves its place in history as the birthplace of the modern civil rights movement for many reasons.

First and foremost, the Montgomery Bus Boycott showed the importance of having a local base when attempts were made to fight segregation. The Montgomery boycott was truly local in nature, with local leaders making all the key decisions. Certainly without the changing national legal environment reflected in key court decisions, most notably Brown v. Board of Education, the Montgomery boycott likely would have achieved nothing more than a few concessions from city officials. Surely outside financial help and even outside advisers, such as Glenn Smiley of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, were crucial to the boycott’s success, But that does not change the fundamental nature of the Montgomery Bus Boycott as a local movement led by the local black community itself.

The Montgomery boycott also showed the importance of the black community presenting a united front. This is not to say that frictions did not arise in the Montgomery movement; they did, and sometimes they were serious. For instance, during the midst of the boycott, a black minister who was a board member of the Montgomery Improvement Association alleged that the group was mishandling funds. Some disagreement also arose between the ministers who led the MIA and lay leaders of the boycott over the direction it took. But for the most part, those schisms were set aside for the good of the cause or at least kept within the movement, and a united image was projected to the outside. That was a crucial reason the Montgomery Bus Boycott captured the imagination of the world.

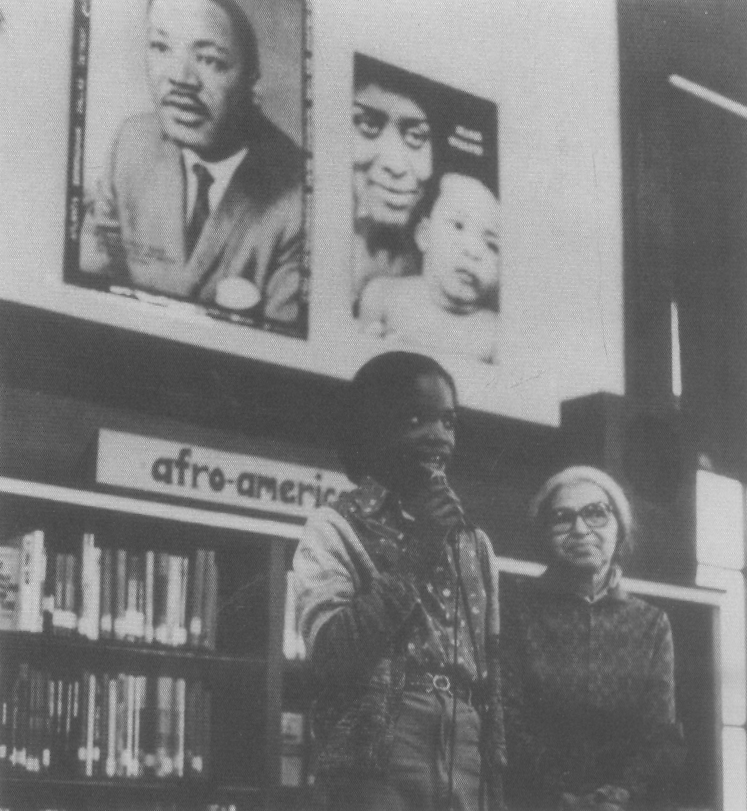

The boycott also catapulted the Rev, Martin Luther King Jr. into the national and international spotlight. King became the face and, more importantly, the voice of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement until his assassination in 1968. E.D. Nixon often said that the focus should not be on what King did for the people of Montgomery but on what the people of Montgomery did for King. While that may have reflected Nixon’s resentment later in life for his comparative lack of recognition for years of working for the betterment of blacks, he still had a point. Without the Montgomery Bus Boycott, King almost certainly would not have become the leading civil right figure of the 20th Century.

One way the Montgomery Bus Boycott directly affected the Civil Rights Movement long after the boycott ended was by giving rise to the creation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Under King’s leadership, the SCLC supplanted the NAACP as the leading civil rights organization of the 1960s.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott also gave rise to the concept of mass nonviolent confrontation as a means of changing legal and societal norms without creating a backlash among the potentially sympathetic majority. The concept was far from new, but the Montgomery boycott showed that it could work in America. King kept it as a focus of the work of the SCLC, and it remained the primary strategy of the civil rights movement for decades.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott deserves its place in history because it was the laboratory where the strategies and tactics of the looming civil rights movement were developed and tested.

It would not have succeeded were it not for the courage and hard work of thousands of people. Some of them would become national civil rights icons, such as Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and Ralph David Abernathy. Others would be lesser known, but still widely honored figures, such as E.D. Nixon, Fred Gray, Jo Ann Robinson, and Robert Graetz, to name a few.

But by far, the most important figures of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the ones who made it happen, are the tens of thousands of unnamed black Montgomerians who from December 5, 1955, until December 21, 1956, walked their way to freedom.