The Montgomery Bus Boycott that began on December 5, 1955, would last for 381 days, a span during which life for virtually every black Montgomerian changed dramatically.

It may be difficult 50 years or more after the boycott for younger Americans to grasp Just how a bus boycott could so fundamentally affect the lives of so many residents of a city. The bus system was the primary means of transportation for the majority of black citizens, who owned relatively few private vehicles. Researchers estimate that some 17,000 blacks took part in the boycott initially, although the numbers quickly grew because of action by the bus system itself. Shortly after the boycott ended, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. claimed that 42,000 blacks took part.

A few days after the boycott began, bus officials asked the City Commission for permission to close routes to many of the primary black communities, arguing that the boycott had made service to those areas no longer financially attractive. 80 in those parts of town, even the handful of blacks who might have wanted to use the buses could not do so.

Several black taxi companies existed in the city, and for the first few days of the boycott these helped to absorb former bus riders looking for alternative transportation. Boycott leaders persuaded most of these companies to charge only 10 cents per ride during the hours most blacks were going to and corning from work. But a few days into the boycott, city officials started to enforce a previously ignored city ordinance that set minimum fares at 45 cents. That priced taxi rides on a daily basis out of the reach of many blue-collar blacks.

Georgette Norman, now the director of the Rosa Parks Museum at Troy University in Montgomery, was nine years old during the boycott. While she did not have to routinely walk to school because her family had a car, she does recall a day that “everybody was supposed to walk, whether you had a car or not.”

“We lived on the west side, but I went to school on the east side. My father and mother worked on the East side, so it meant that we had to walk From the west side to the east side. I recall that it was really fun because you would meet people along the way.”

The boycott wasn’t fun for most adult African Americans in Montgomery, Not only were many concerned about losing their jobs because they could not get to work, but also they feared that some employers would retaliate simply because they cook part in the boycott.

Norman remembers that her own father, who managed Tulane Court, a city housing project, received such a threat of retaliation after he attended a mass meeting.

“They called my father and told him that they understood he attended a mass meeting the night before, and that if he valued his job he would not be going to any more meetings,” she said.

At the urging of black churches, blacks who owned cars gave rides to friends and neighbors, Johnnie Carr, a friend of Rosa Parks who served as president of the post-boycott Montgomery Improvement Association for more than three decades, recalls spending time each day giving people rides.

“We had people who would walk miles to get to their destination rather than ride the buses,” Carr said. “My husband and I both had cars since we were in the insurance business, and we would go by on the way to work to see if we could drop anybody off.” Hundreds of other middle-class blacks-pastors, doctors, teachers and college professors-did the same.

Interestingly early in the boycott many white citizens also helped provide transportation to and from work for their black employees, especially domestic workers. While a few whites supported the boycott, most of them were motivated either by sympathy to the plight of their black employees or just wanted their work to be done.

But over time, the number of whites providing transportation dwindled under pressure From others in the white community. The varied social and business pressures brought against sympathetic whites were captured by the 1990 movie, The Long Walk Home, starring Whoopi Goldberg and Sissy Spacek.

Boycott leaders quickly realized that their plans for a more organized alternative transportation system would have to be put into high gear if the boycott were to succeed long term.

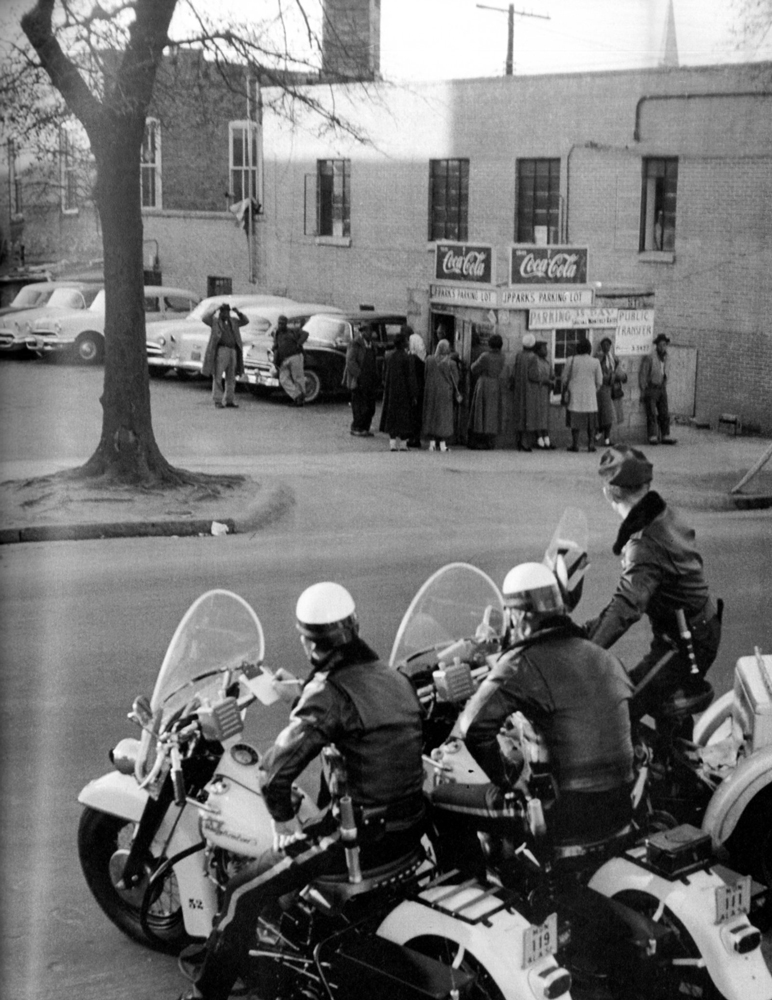

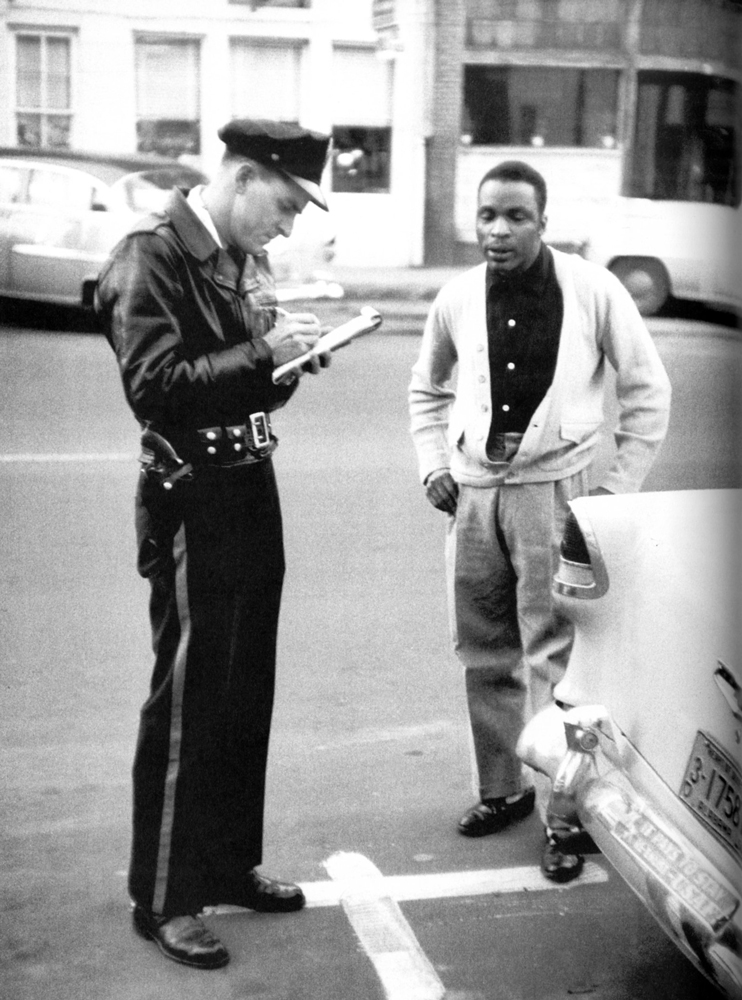

Churches bought cars and station wagons specifically for the transportation system. Pickup and delivery points were designated around the city and routes were established, People who needed gasoline were provided fuel. The city police harassed the system by enforcing laws against crowding and a variety of minor traffic violations, but the car pool succeeded anyway. It soon developed into an efficient and cost-effective means of transportation, with some observers noting ironically that it solved several of the transportation problems with which the bus system had struggled for years.

As the boycott wore on, intimidation tactics took various forms. The most sweeping official action designed to deter boycott leaders came in February 1956, when the Montgomery grand jury indicted 89 boycott leaders-s-including King, Parks, Abernathy and most of the other participating black ministers. The charges were based on a 1921 state stature that barred boycotts without “just cause.” Those indicted were arrested over the next few days, booked and released on bond.

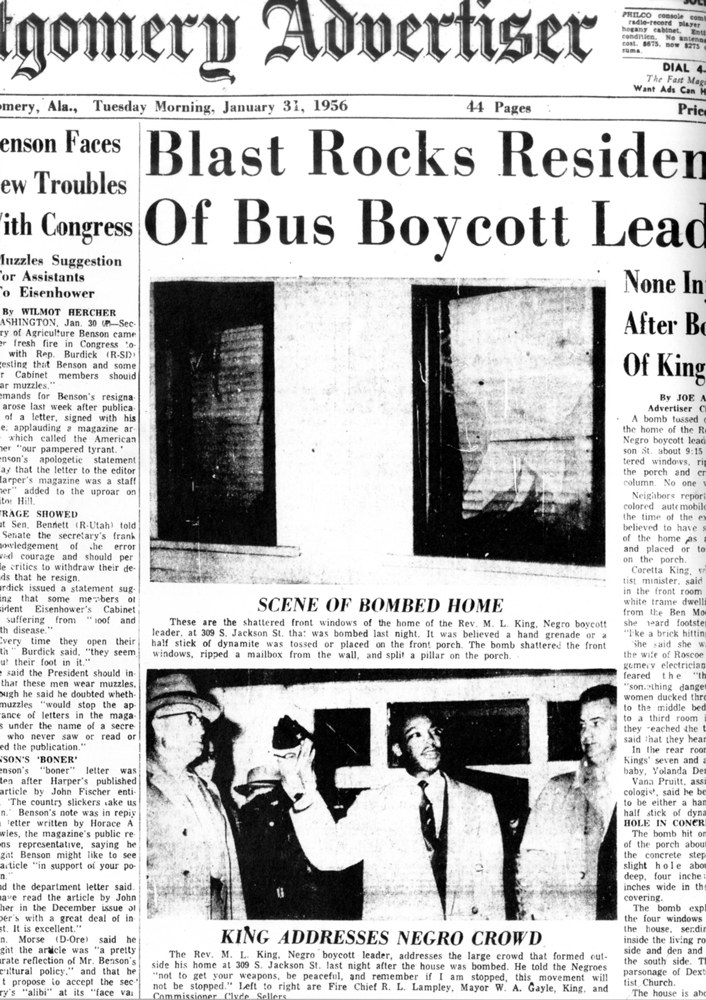

But as official tactics failed to discourage the boycott, unofficial intimidation soon took a more dangerous turn. In January, the parsonage in which King and his family lived was bombed. Coretta Scott King and the Kings’ two-year-old daughter Yolanda narrowly escaped injury. King stood on his damaged porch and persuaded an angry crowd of blacks, some of them armed, not to respond with violence. The next night, E.D. Nixon’s home was also bombed.

In August, the home of white Lutheran minister Robert Graetz also was bombed. Graetz, whose church was all-black, was probably targeted because he was the only white member of the board of the Montgomery Improvement Association. His home was later bombed again.

Graetz said his greatest concern was for his children, especially after he and his wife received anonymous calls pointedly mentioning what his children had been doing just moments before. The callers were trying to intimidate Graetz by showing that his children were under observation and vulnerable.

Graetz’s wife, Jeannie, said: “I had the feeling they were just out to scare us and nothing bad would happen. I had to make myself feel that way.”

The Rev. Graetz said that in the end, they simply had to trust in God to protect them, Even past the end of the boycott, the violence continued. In addition to bombings, King’s home was shot into. After the boycott came to a close, snipers shot into buses in black communities, at one point hitting a young black woman, Rosa Jordan, in the legs. Her injuries were not life-threatening.

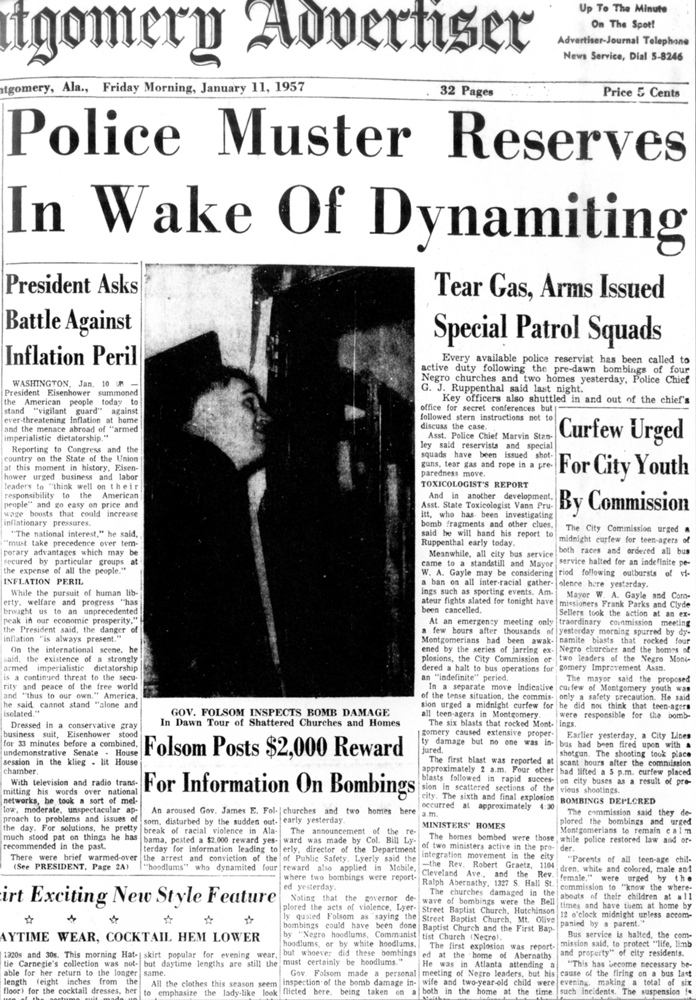

The worst single night of violence occurred on January 10, 1957, a few weeks after the end of the boycott and segregated seating on buses. Four black churches and two homes were bombed, including the Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s church and parsonage.

“Dr. King used to talk about the reality that some of us were going to die, and that if any of us were afraid to die we really shouldn’t be there,” Graetz said.

But amazingly, King was wrong. Despite the violence, no one died in the boycott, and only Rosa Jordan was shot.

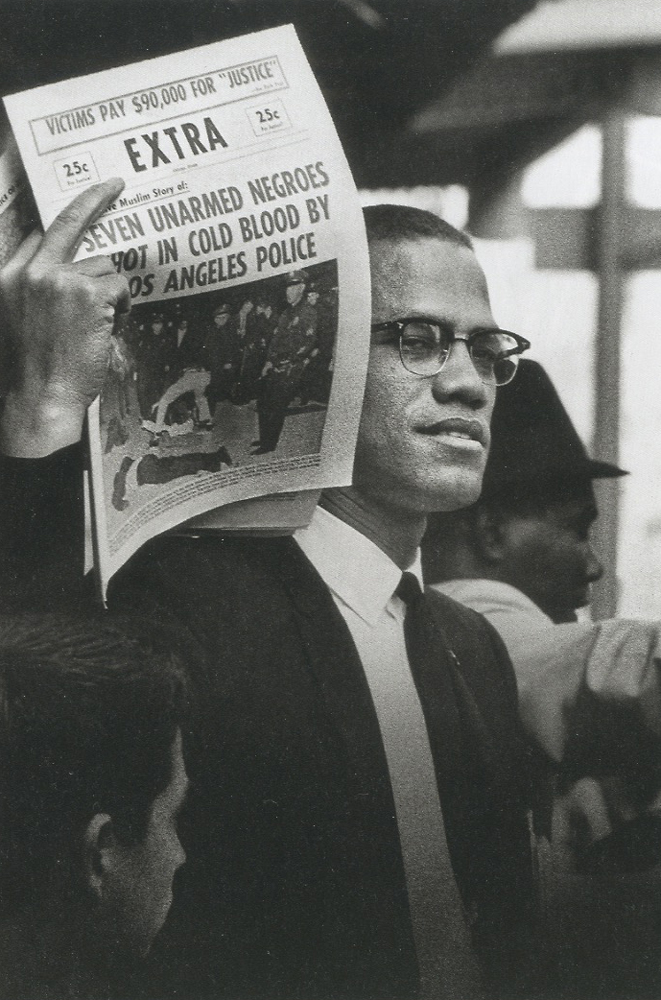

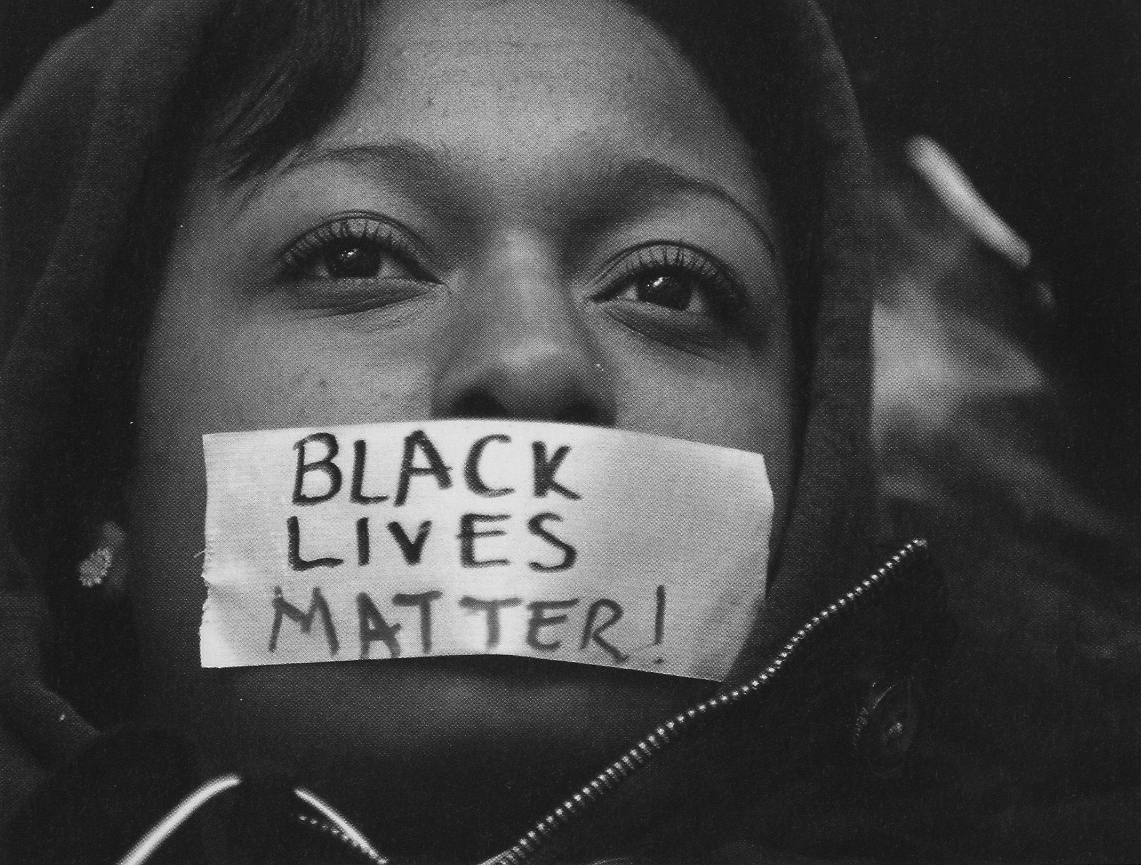

The intimidation tactics failed to significantly deter any black boycotters. Instead, for the most part, they spurred black Montgomerians to greater efforts.

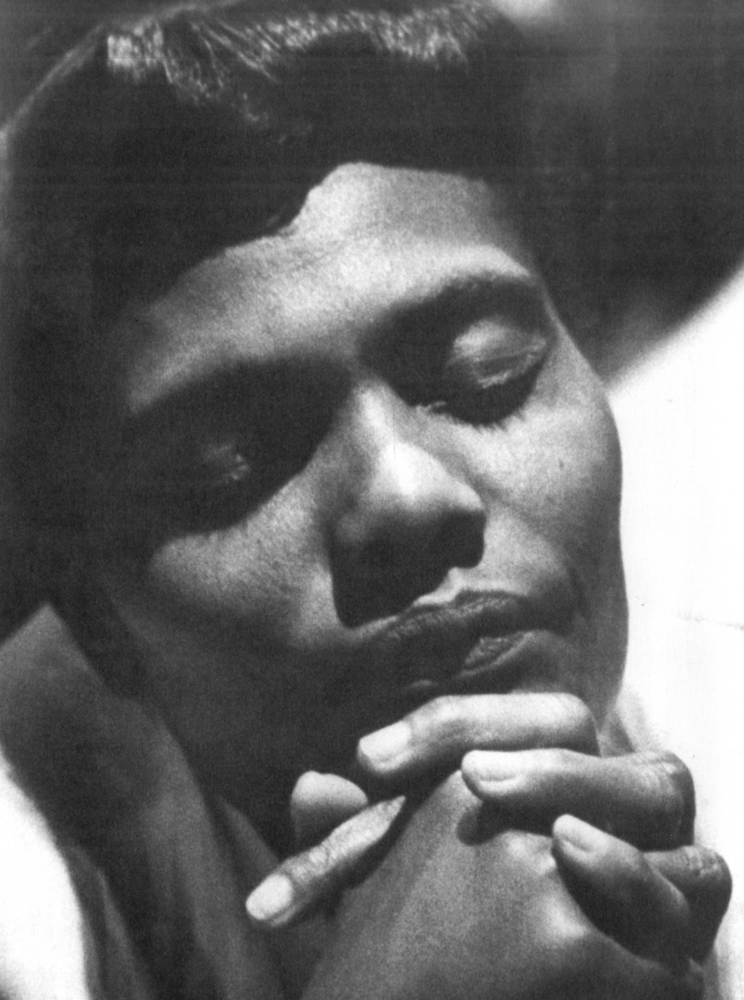

In an analysis of the Montgomery Bus Boycott printed in the journal Liberation in 1957, King wrote: “Because the mayor and city authorities cannot admit to themselves that we [black Montgomerians] have changed, every move they have made has inadvertently increased the protest and united the Negro Community.”

King used his arrest for going 30 mph in a 25 mph zone “just two hours before a mass meeting” as an example, saying that after his arrest “we had to hold seven mass meetings to accommodate the people.”

He also said the bombings of his and Nixon’s homes “brought moral and financial support from all over the state.”

In fact, as the black community stood steadfast against intimidation and violence, support for the cause spread not just over the state, but throughout the nation.