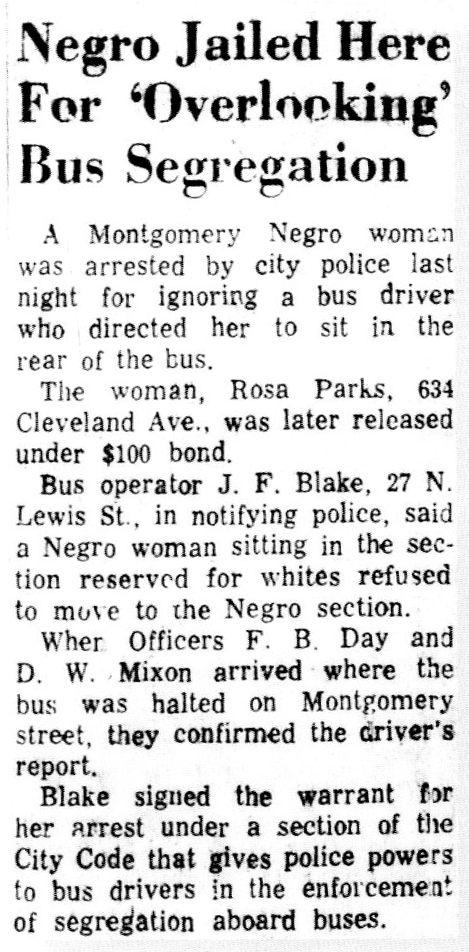

When Rosa Parks left her job as a seamstress to catch a bus on the afternoon of December 1, 1955, she didn’t set out to make history. She was tired and Just wanted to go home.

But when the bus driver asked her to give up her seat so that a white man could sit there, she couldn’t bring herself to do it.

“I didn’t get on the bus with the intention of being arrested,” she often said later. “I got on the bus with the intention of going home.”

Neither did she sit in the section at the front of the bus reserved for white passengers, although the story is sometimes told that way, She said she took the only remaining sent in the section for blacks.

“The back of the bus was all filled up with black people already,” she said,

But the driver noted that there were two or three white men standing, so he asked that four black passengers, including Parks, give up their seats so the whites could sit,

(Interestingly, the driver violated the bus regulations when he did so, since blacks seated in the section set aside for them did not have to relinquish their scats to whites unless there were ether seats available.)

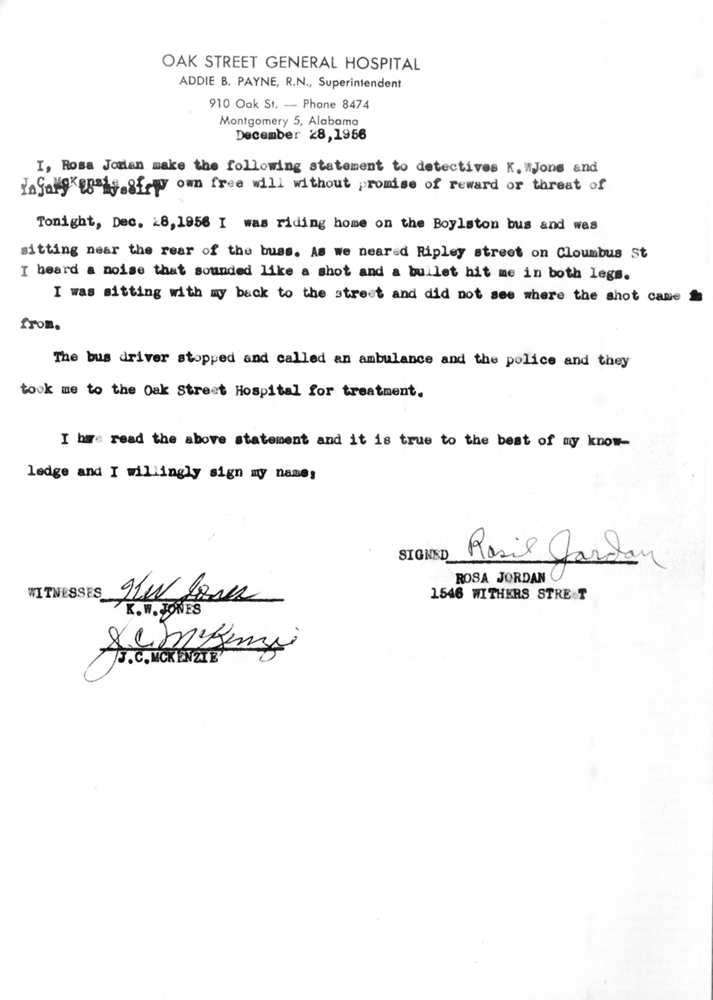

The other passengers reluctantly stood and moved back, but Rosa Parks did not. While she had no way of knowing her action would set in motion the pivotal Montgomery Bus Boycott, she knew one thing. Her own personal bus boycott began that day.

“I knew that as far as I was concerned, I would never ride on a segregated bus again.”

While her stand was on the one hand a spur-of-the-moment decision, it still was not done lightly. Although Rosa Parks was a quiet and seemingly unassuming woman, she had been involved in civil rights activism for several years, although in a much less central role than the one she was about to assume. In a sense, her whole life had prepared her for this moment.

As a young girl, she had seen the results of segregation growing up in the small rural community of Pine Level, Alabama. There she attended elementary school in a shack with only a wood stove for heat, while her white counterparts attended a newer school with central hear. When she moved up to a private school for African-American girls in Montgomery, she saw her white teachers snubbed in the white community because they taught at the school. As an adult, she was active in voter registration drives and the NAACP, serving as president of the NAACP Youth Council. She also acted as secretary to E.D. Nixon, who for years prior to the bus boycott was the leading civil rights activist in Montgomery and one of the leaders in the state. She had attended a training workshop for activists at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, where she had been stirred by messages of equality.

Earlier on the day of her arrest, she had lunched in the office of young black attorney Fred Gray, who later led the legal team that challenged bus-segregation policies. Gray recalls in his memoir, Bus Ride to Justice, that in similar shared lunches in his office, he and Parks had discussed the earlier arrest of 15-year-old Claudette Colvin for refusing to give up her bus seat and even the possibility of a boycott. So while her refusal to move to the back of the bus was not premeditated, it also should not have been a surprise to those who knew Rosa Parks best.

In 1956 she told radio interviewer Sidney Rogers, “The time had just come when I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed, I suppose.”

So when ordered by the bus driver to give up her seat, she did not move, And she still did not move when the driver threatened to have her arrested.

She later told the Associated Press: “I told him to go on and have me arrested. I wasn’t frightened. I felt somewhat annoyed at being inconvenienced by not being able to got home as I had planned.”

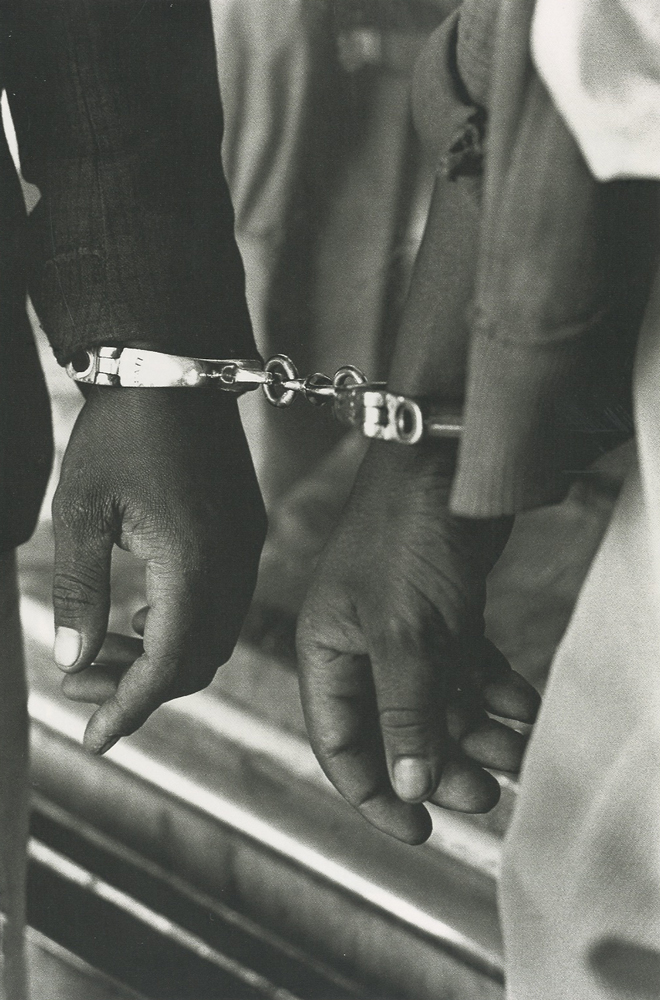

Parks was booked at the Montgomery police station. She was quickly bailed out of the city jail by her friend E.D. Nixon and white attorney Clifford Durr, a former high-ranking official in the Roosevelt Administration. They were accompanied by Durr’s wife, Virginia, a friend of Parks who was active in anti-segregation efforts in the South and a sister-in-law of Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black.

Parks, Nixon, and the Durrs returned to her home, where Nixon overcame her husband’s objections and persuaded Parks to allow her arrest to be used as the basis of a challenge to bus segregation laws.

Parks, who was always modest about her role in the Civil Rights Movement, later gave credit to a higher power for her decision not to give up her scat, saying that as she sat there she recalled Bible lessons that taught that people should stand up for their rights as the children of Israel stood up to Pharaoh. She was quoted in the Montgomery Advertiser years later as saying: “I was fortunate God provided me with the strength I needed at the precise time conditions were ripe for change. I am thankful to him every day that he gave me the strength not to move.”

Johnnie Carr, a longtime friend of Rosa Parks who played a key role in the desegregation of Montgomery public schools several years after the bus boycott, simply describes what happened on December 1: “A woman sat down and the world turned around.”

It did not take long for that movement to begin.

There were many forces in Rosa Parks’s early life that helped to forge her brand of quiet activism.