Knowing Their Space: Signs of Jim Crow in the Segregated South

by Elizabeth Guffey

Jim Crow Law

Jim Crow laws were relatively rare before 1895, when the African American Homer Plessy lost his Supreme Court suit against the State of Louisiana. Plessy’s lawsuit was intended to bring attention to an 1890 Louisiana law that dictated segregated transport; ironically, the authority and publicity of the Supreme Court judgment helped concretize the concept of “separate but equal” spaces, providing firm legal footing for institutionalized racism in the United States. Southern segregation signs reflect a pervasive patchwork of local and state laws that formed a racialized order throughout the region.

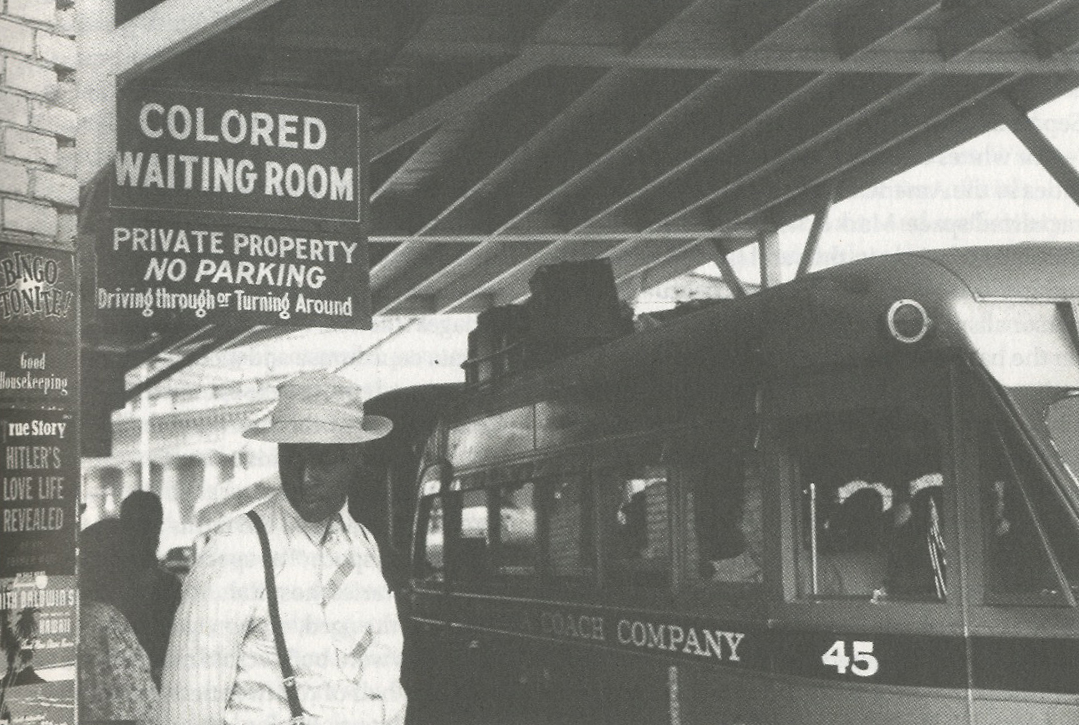

In the decade following the Plessy ruling, state and municipal legislators throughout the South passed a spate of new laws that regulated daily life; these mandates were so pervasive that the phrase “Jim Crow law” first appeared in the Dictionary of American English in 1904. Many of the most prominent segregation laws dictated separate spaces on public transportation, including trains, streetcars, and trolleys. By 1909, 14 state legislatures enacted laws in which passengers were assigned separate coaches, compartments, or seats on the basis of race. These laws were first enforced by conductors and ticketing agents, whose duties included maintaining segregated spaces; railroad companies could be fined as much as $100 a day for violating segregation laws.

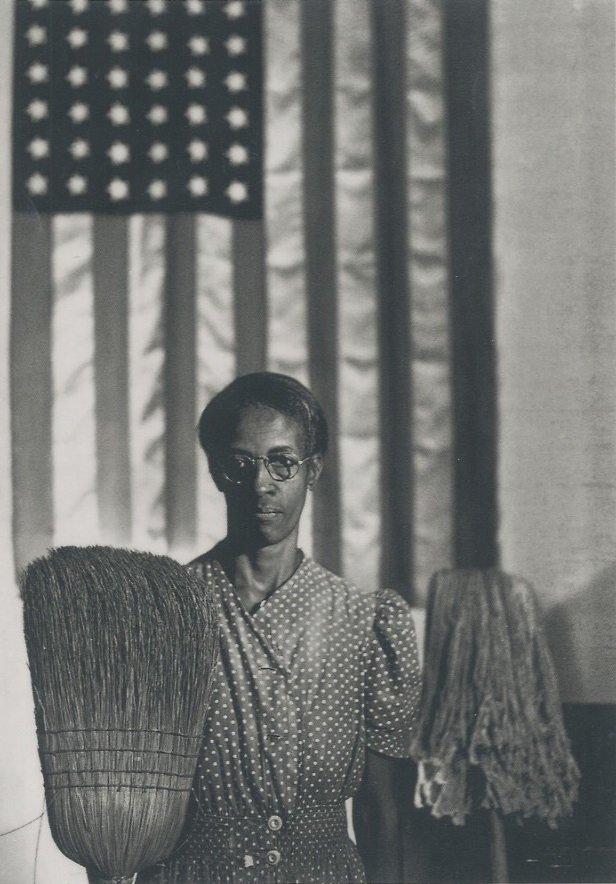

But Jim Crow legislation did not end there. By the time the United States entered into the First World War, laws in Southern states ordered racial segregation in marriage, education, and health care. Laws also molded the shape of daily life in other ways, as state and local prohibitions prevented different races from renting in the same building and required that movie theaters seat the races separately, that amateur baseball teams play on diamonds separated by two or more blocks, and that restaurants install partitions at least seven feet high between areas reserved for white and non-white diners. In the post-Civil War South, reformers argued that transportation, education, and infrastructure would transform this impoverished region. Little did they anticipate, however, that the very trains, street cars, parks and hospitals that these reformers helped introduce and develop would become part of complex systems of racialized wayfaring. The rapid growth of cities like Atlanta shows just how closely Jim Crow segregation followed Southern urbanization. This emblem of the New South also became one of the most segregated cities in the nation. Jim Crow became the very public face of new civic ordinances that extended not only to public spaces under the city’s jurisdiction (e.g., parks and libraries), but also to privately-owned ones like saloons and restaurants. Legislation mandated that black barbers could not cut the hair of white women or children under 14, and separate Bibles were required for white and lack witnesses in the Atlanta court system. In cities like Atlanta and Birmingham, taxis had to be labeled by race “in an oil paint of contrasting color,” and laws stipulated that drivers had to be the same race as their customers!

Separation of Public Space in the New South

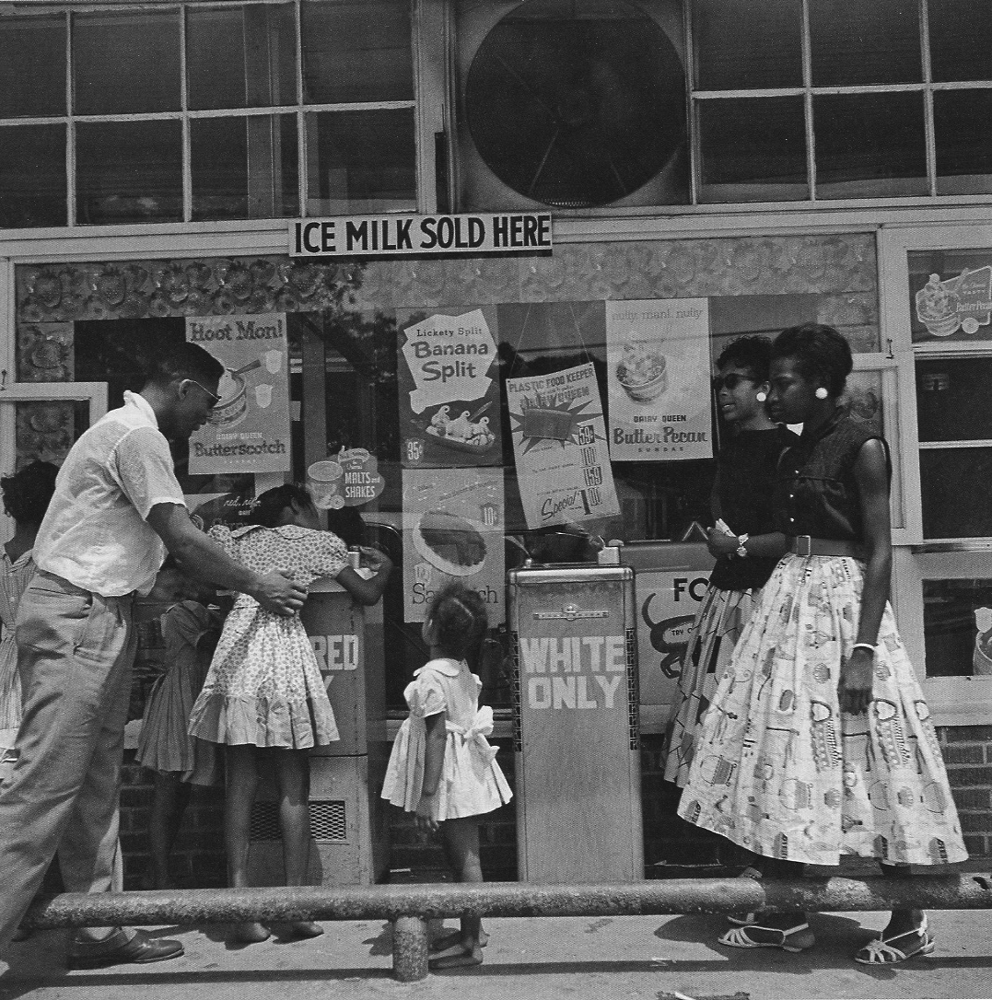

For whites and blacks, most day-to-day activities in the American South were carried out in racialized space. Mark Schultz notes, however, that race relations in the rural (as opposed to urban) South were marked by a “culture of personalism ”, which shaped racial interaction on the basis of close relations and custom, rather than on the law! In these settings, Jim Crow space was rarely labeled; tradition alone, for instance, clearly dictated that blacks were to step aside for passing Whites on a sidewalk. Many small towns enforced Saturdays as “Black People’s Day ”, when town business districts were given over to weekly shopping trips by African-Americans flush with Friday paychecks. County fairs often sold tickets marked “colored” to African-Americans, and they would be open to whites on Tuesdays through Fridays, thus leaving Saturdays for blacks. Wilhelmina Baldwin, a teacher from Waynesboro, CA, remembered that the entire town became white after dark: “They also had a curfew for blacks. If you were just a run-of-the-mill black, your curfew was at 9:30. If you were, you know, what they called an educated black, you could stay out’til 10:30. If you stayed out beyond 10:30, you had to have a written statement from the chief of police.” Because race relations were relatively settled in less densely populated rural and farming districts, wayfinding systems in these areas were often unnecessary. Most residents living in these small communities were born there, and few feared getting lost, either in physical or social terms. Outsiders who stumbled into small and often isolated towns could read the unwritten signs that signaled segregation. George Butterfield, an African-American Supreme Court judge and then congressman in North Carolina, noted that, “when you live in the South and have been in the South all your life, you could find [places to eat and sleep] instinctively.” Nevertheless, as the towns and cities of the new urbanized South grew, residents encountered unfamiliar problems; here, where strangers could casually meet and interact, traditions were not established. Complex racialized spaces had to be negotiated, and expectations for behavior had to be articulated. Restaurants frequently erected wood screens through their dining rooms, and train cars were sometimes designed with panels that divided carriages into two distinct compartments; in a Virginia courthouse and along a South Carolina swimming shore, ropes separated the black and white sections of the court and the beach. And, as architectural historian Tim Weyeneth has demonstrated, large-scale building projects increasingly dictated the terms and conditions of racialized space as specifically-designed schools, libraries, hospitals, mental hospitals, homes for the aged, orphanages, prisons, and cemeteries were built across much of the South in the first half of the twentieth century. In Richland County, SC, for instance, the 1940s remodeling of Columbia Hospital by Lafaye and Associates included the construction of a smaller, separate hospital two blocks away from the main, whites-only complex. When building such completely separate spaces was deemed too costly or otherwise inefficient, structures were commonly designed to include both separate and shared spaces under a single roof. Hospitals, for instance, would have segregated wings, public housing would be divided into separate districts or even units, and public parks were fenced or roped into grounds and facilities designated as “white” or “colored.”

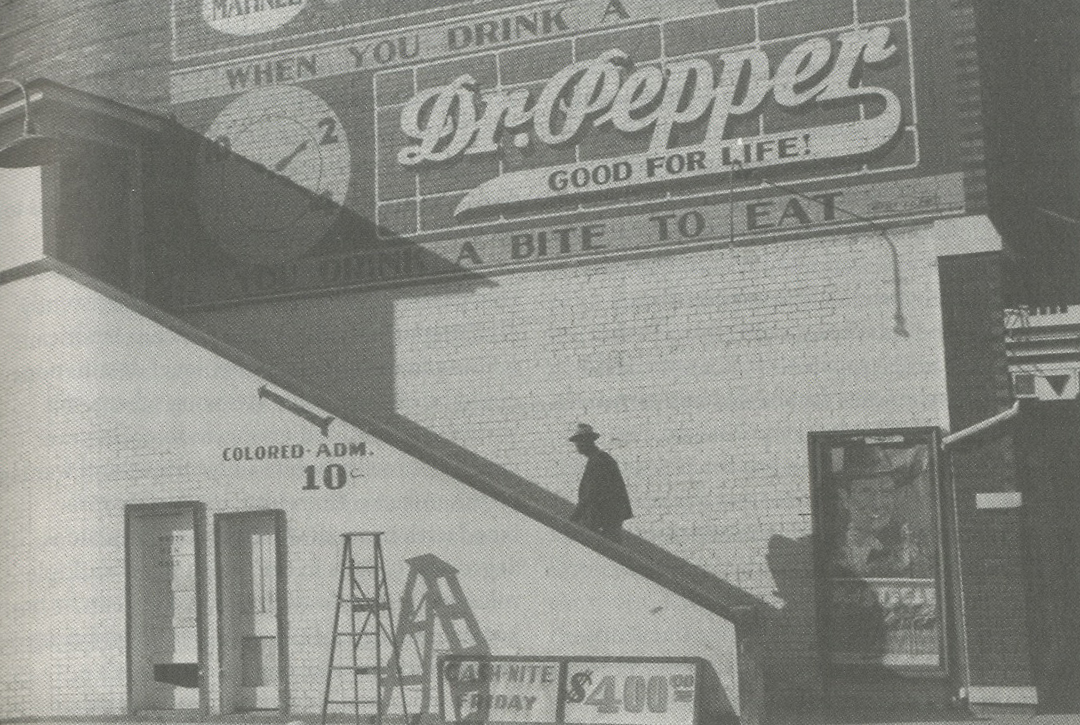

Although no urban planner designed fully segregated cities, architects clearly planned buildings that not only included separate black and white spaces but also ensured segregated routes for finding those spaces. For example, architectural drawings of cinemas designed by Erle Stillwell in North Carolina, reveal not only separate African-American seating areas but also carefully planned systems of diversions, including entrances, and passageways explicitly designed to lead non-whites away from white-designated spaces. When Still well designed Raleigh’s Ambassador Theater in 1938, he planned for African-Americans to enter the building at a side entrance. Patrons climbed a discrete staircase that led them to a landing housing what Stillwell’s plans called the “colored” box office. Up another flight of stairs, African-Americans could find toilets, a small room for the use of “colored ushers ”, and balcony seats. Although the Ambassador Theatre was tom down in 1979, the relatively complex passage by which African-Americans entered the movie house from the street, then found the “colored” box office, then found their seats and separate facilities suggests just how byzantine Jim Crow wayfinding could be. Recalling a less carefully planned theater in Waynesboro, GA, Wilhemina Baldwain described exiting a matinee showing of a film in the late 1930S ; white patrons insisted on not even seeing African-Americans who’d attended the same show. “There was usually nobody there. We’d go to the ticket window, buy our tickets, and go upstairs (to the segregated seating for blacks). And likewise there was nobody there when we would come out. Well, one day there was a little white boy... eight or nine years old... he was standing there, with his hands across the door... and so when we got to the bottom of the steps I said “excuse me please.’ He said “Niggers can’t come out till the white people get out.” At least a decade older than the boy, the movie-going Baldwin talked the boy down but recalled seeing other African-Americans obeying his directions.

Blocked doors, the construction of isolated buildings and the erection of barriers were useful but only effective for a limited time to segregationists. Similarly, duplicate architectural features such as entrances, exits, elevators, and stairwells, might have served immediate racist ends. However, if they lacked specific labels to indicate their function, such structural elements lost their Significance. When President Franklin Roosevelt inspected the Construction of the Pentagon in Arlington, VA in 1941, he questioned the inclusion of “four huge washrooms placed along each of the five axes.” The astonished president, a native of New York, was informed that Virginia’s segregationist legislation “required as many rooms marked “Colored Men’ and “Colored Women’ as “White Men’ and “White Women.” Military officials, heeding larger issues of waste and inefficiency, ultimately disregarded the local law ; signs were never mounted on the doors and the duplicate (spaces lost their initial meaning.

Finding the Way to Jim Crow Space

While Arthur and Passini suggest that wayfinding is a form of spatial problem-solving, they insist that successful wayfinding systems do not rely on architecture or barriers alone; instead, they require the consistent identification and marking of space. Without signage, the Pentagon’s Jim Crow bathrooms lost their meaning. Reading the plans of Raleigh’s Ambassador Theater, with its carefully designated “colored box office” and room for “colored ushers,” makes clear how the architect created a labyrinth of passageways that guided African-American customers away from whites. But without labeling, the theater’s maze of passageways would have been incomprehensible.

As a field, wayfinding was in its infancy when Jim Crow laws and signs were at their height. However, as the older Jim Crow signs make clear, by the early twentieth century, public signage could construct complex systems when supported by custom and law. Of course, segregation was so pervasive a system that whites also abnegated a degree of freedom by embracing it. They, too, arranged their shopping around “black days” in town and avoided taking colored taxis. Jim Crow signage dictated both white and black space. The white writer and sociologist Kathryn DuPre Lumpkin recalled, “as soon as I could read, I would carefully spell out the notices in public places. I wished to be certain we were where we ought to be. Our station waiting rooms— “For Whites.” Our railroad coaches— “For Whites.” White passengers could be ejected from trolleys and buses when they chose to sit in the back rows. Jennifer Roback, for instance, points to the case of J. M. Dicks, a white Augusta, GA ironworker who violated state segregation ordinances by insisting on sitting in the back of a streetcar in May 1900. Arrested by the train’s conductor, Dicks explained to the court “When I got off from work yesterday afternoon I was feeling tough and looking tough… I saw some ladies up ahead and did not want to sit by them looking like I was.” Calling the conductor a “d--- fool ”, the passenger was faced with a perplexing situation: violating social custom on the one hand or transgressing the law on the other.

Despite the limits that also affected them, whites—especially men— were often accorded a degree of flexibility in infringing on segregated spaces. For example, where African-Americans were strictly prohibited from whites-only passenger cars on trains, the colored cars could double as smoking cars (for whites) or as spaces where the white crew could lounge and relax. Ticketed white passengers could pass through the Jim Crow cars, but African-Americans were often prohibited from walking through those set aside for whites. Indeed, public space was often deemed “white” by default, unless otherwise designated.

Even when signage clearly circumscribed white behavior, the legal system often treated white’s infractions lightly. For instance, when a municipal judge heard the case of J. M. Dicks, the Augusta, CA ironworker who insisted on sitting in the colored section of a city street car, the judge publicly belittled the conductor and arresting officers for their lack of judgment and dismissed the case. Jim Crow signs dictated the decisions and actions of both black and white Southerners, but there was no doubt who ultimately held power in these situations.

Decision-Making in a Jim Crow World

Especially for African-Americans, finding the way to one’s “own” space in the Jim Crow South clearly could be a complex and counter-intuitive process. However, failing at it also carried high stakes. While theorists today describe wayfinding as a process that can keep people from being lost and afraid, in the Jim Crow South, mistaking a turn or using the wrong facilities could result in violence or death.

Passini suggests that wayfinding involves a hierarchy of decision making that begins long before an individual starts to move through space. Choosing a destination—that is, deciding to move from point A to point B— is a high-order decision. The scale of the trip is unimportant; the resolutions to shop at a store down the street or to take a trip across the country both reveal that a high-order decision has been made. In the South, the very choice of where one could and could not go was complex; a host of semi-public spaces (e.g., white churches, beauty parlors or funeral homes) were simply off limits to blacks. Indeed, most African-Americans in the rural South relied not only on signs but also on a series of learned codes of conduct, habituated through years of living in racialized space and passed from one generation to the next. This learning was part of what black activist and academic Cleveland Sellers calls a “subtle, but enormously effective, conditioning process. The other people in the community, those who knew what segregation and Jim Crow were all about, taught us what we were supposed to think and how we were supposed to act. They did not teach us with words so much as they taught us with attitudes and behavior. There wasn’t anything intellectual about the procedure. In fact, it was almost Pavlovian.”

As an early, if incomplete, form of wayfinding, the Jim Crow spatial system complicates Passini’s theory. In his view, wayfinders make high-order decisions in a sociological vacuum; but unlike Passini’s empowered wayfinders, African-Americans who understood the shaping of Jim Crow space automatically formed their higher order decisions around Jim Crow exclusion. Certain destinations were automatically off limits; others were simply avoided. Remembering these limitations, Wilhemina Baldwin recalled how her parents shielded their children, avoiding taking them to public spaces dominated by whites. “There were just certain things that we did not do,” she recalled. “For instance, going to wherever we went out of town, they took us. We never had to go to the bus station for anything. Until I got to be 10 years old, they didn’t take me to buy shoes. They bought my shoes. And if they didn’t fit, they’d take them back and get another size. They bought the clothes for all of us like that. So we didn’t get into the stores to have to deal with the clerks and whatnot.”

Planning Action in Jim Crow Spaces

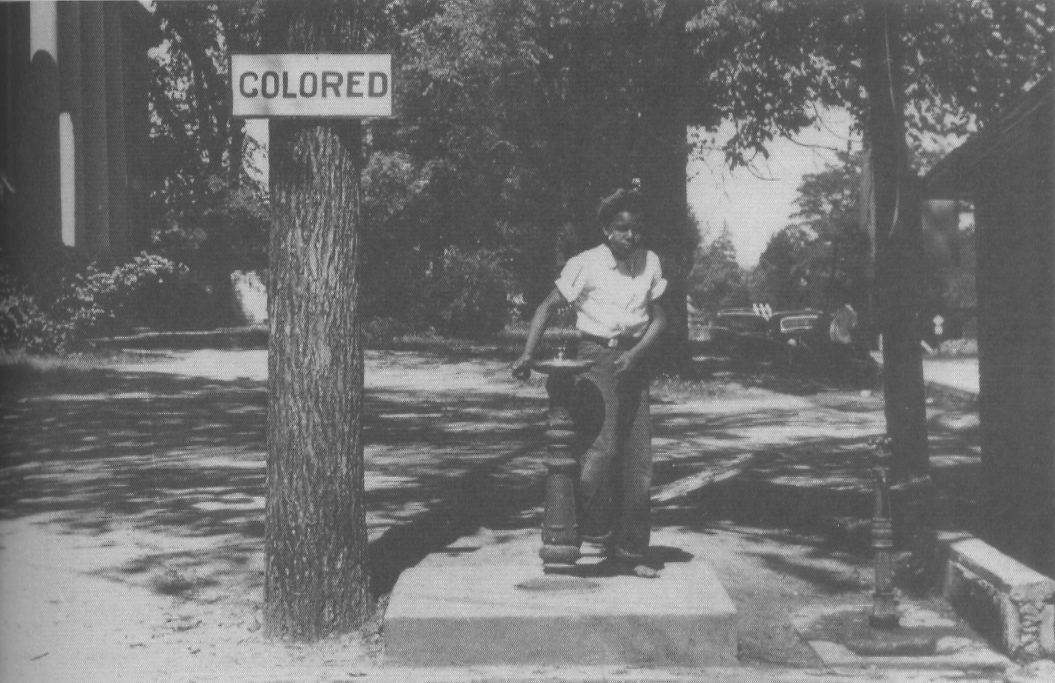

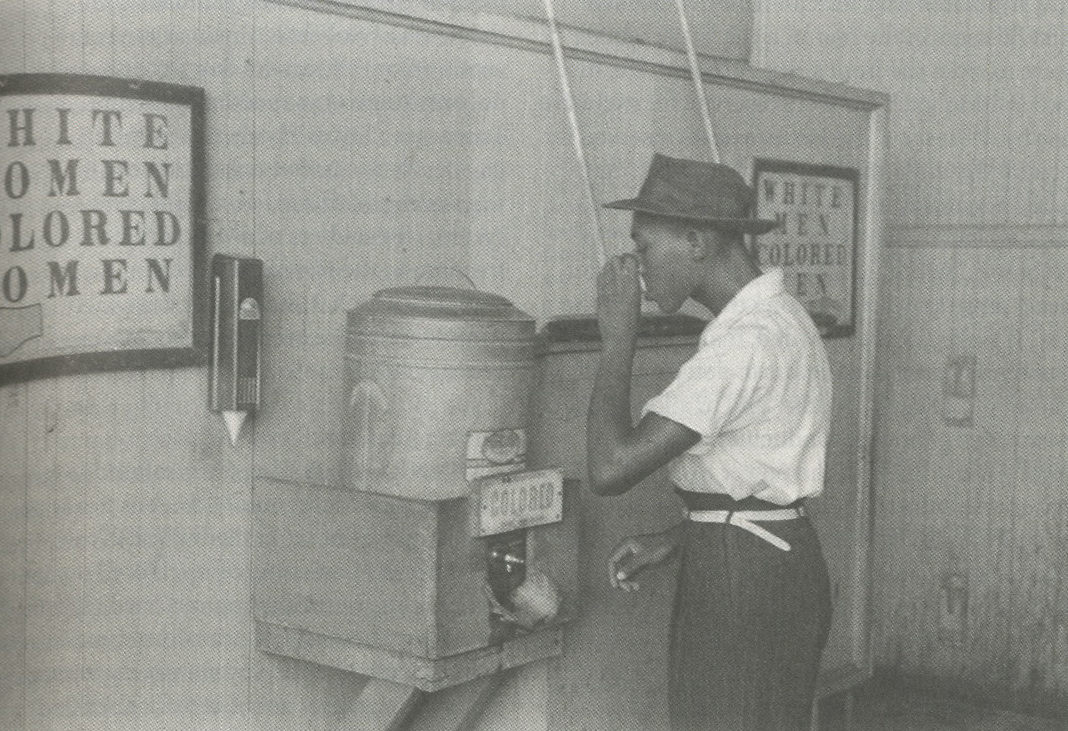

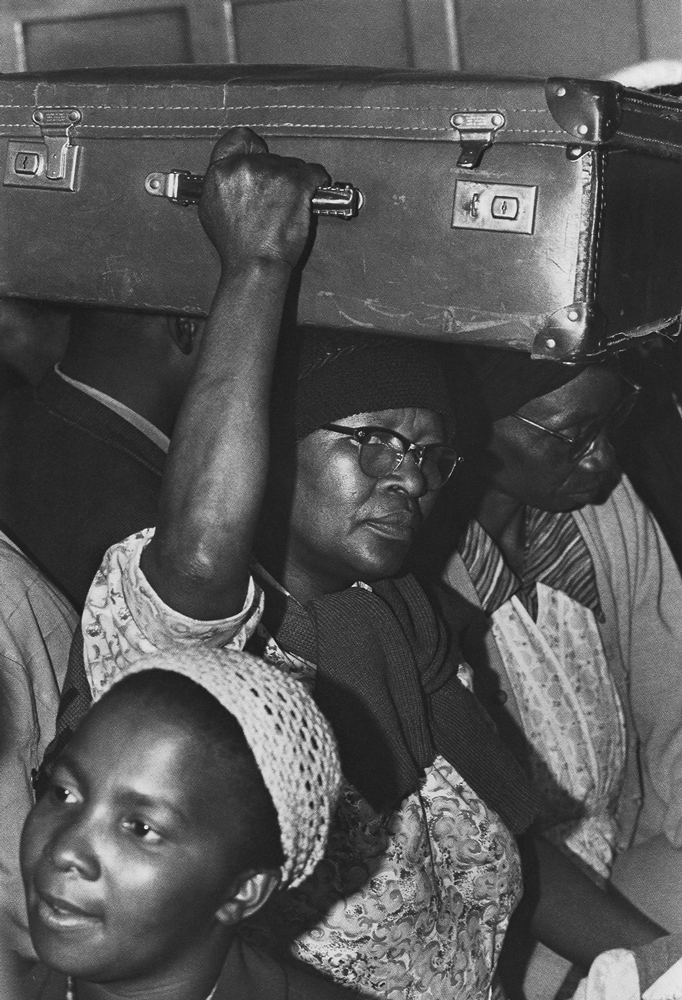

African-Americans in the Jim Crow South might have practiced a highly selective decision-making process, but as Passini reminds us, wayfinding involves more than choosing where to go. Having fixed a destination, the wayfarer then begins executing a series of lower level decisions that make that action possible. For most wayfarers, this planning involves designating a route and developing an action plan. Again, African-Americans chose their routes with care. Long distance car trips through the South were often experienced as a gauntlet. African-American wayfarers needed “exquisite planning,” carefully weighing the need to stop for gas and food in segregated gas stations and restaurants, and often driving for three or four days without stopping, loading up on cold cuts and stuffing ice boxes and lard buckets full of ice to provide rudimentary air conditioning. Even planning simple routes around one’s hometown could be fraught with peril, and many African-Americans chose routes that avoided white spaces altogether. As Ralph Thompson recalled, his parents warily planned his childhood visits to Memphis. His mother, for example, took elaborate precautions to sidestep the “things that would be embarrassing, when they couldn’t fight back… If we went downtown and they had the colored drinking fountain and white drinking fountain, my mother would always tell us to drink water before we left home. So we didn’t get caught into drinking water out.” Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown ran the Palmer Memorial Institute, a missionary-funded school in Sedalia, NC, and she taught her students to develop action plans that worked around Jim Crow restrictions. Taking her students to the movies, for example, she’d rent the entire cinema for the day and avoid the segregated upper balcony. But no amount of careful planning could erase the ubiquitous presence of the signs that shaped the very environment in which African-Americans lived their daily lives.

Navigating a route in the Jim Crow South, however, required African-Americans to maintain constant vigilance. Jim Crow signs exerted their most devastating power at precisely this level, consistently challenging and deflecting African-Americans’ action plans. Indeed, higher level destinations could be chosen while knowing where one would and would not be welcome. However, confronted with “white only” trains and waiting rooms, African-American wayfarers were faced with immediate lower level decisions, Segregation signs in the South filled multiple roles, but in wayfinding terms, they can be broken into two general types: identification signs and directional signs.

Identification Signs

Often called “the building blocks of wayfinding,” identification signs mark out spaces by displaying their name or their function, Since the mid-nineteenth century, in rapidly growing cities like New York and London, public signage proliferated, labeling space and addressing passersby. Simple labeling techniques (e.g. posted street names and addresses, room numbering signs, name plates, and other forms of labeling) became ubiquitous in the United States after the Civil War. But the marking of Jim Crow space was more specific and relied on fairly consistent terms of identification. Clearly understood labels like “colored only” and “whites only” were most common, although some relied on more cursory words, such as “white” or “black.” Such signs routinely rerouted travelers. Directional Signs Coupled with exclusionary phrases, like “Whites This Way” or an arrow with the words, “Colored Dining Room in Rear,” Jim Crow signs not only identified, but also directed. Usually mounted on walls or placed overhead, directional signs dictated who could drink at which water fountain or where to sit in a restaurant.

These directives could also be complex, involving a sequential process of multiple decisions, such as entering a train station through the “right” door, buying a ticket at the “right” window, finding the “right” waiting room, moving from that waiting room to the “right” platform, then finding the “right” train car. At this time, signage systems meant to control behavioral actions (e.g., turning left or going up stairs) were still in their infancy, But simple graphic prompts, such as prominent arrows or the Victorian letter jobber’s pointing finger, or manicules still had the power to shape decisions. Design and Production of Jim Crow Signs While most manufacture signs were produced with standard industrial printing processes, including offset lithography and silkscreen, Jim Crow signs were also customized with stencils and vinyl letterforms and were printed on more permanent materials, including metal and porcelain. At the new Tennessee Valley Authority headquarters, for instance, an imposing “WHITE” sign was crafted in metal and installed above public water fountains, conveying a tangible sense of institutional authority. While the sans serif letters were clearly influenced by the spare, unadorned typographic forms of the emergent Modernist movement, their function was utterly antithetical to the egalitarian, even utopian, goals that drove designers such as Jan Tschichold and Herbert Bayer to develop typefaces that would promote universal legibility.

The tradition of hand-made, and especially painted, Jim Crow signs continued until the Civil Rights movement obviated the entire system in the early 1960s. Nevertheless, as mass-produced signs became more and more common, the increasing consistency of segregation signs’ appearance began to convey a kind of uniform identity, flatly assigning races to different spaces. Nevertheless, this increasing uniformity was misleading: the South’s segregation laws and customs were inconsistent and inconsistently applied; in addition, the signs’ authoritative appearance belied a system of racializing space that, while pervasive, was far from universally understood.

Ending Jim Crow Signs

When Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, AL, bus to a white man in 1955, she sat in the bus’s fifth row— officially the beginning of its colored section but also one of the ambiguous “twilight zones” that a conductor might transform from “black” space to “white” space by simply repositioning a printed sign. Her act of civil disobedience reflected the increasing questioning of Jim Crow segregation and the system it represented by both whites and blacks. Indeed, Parks’ action was well timed; after 1946, when the Supreme Court’s decision in Morgan v. Virginia ruled segregation illegal on interstate bus travel, Jim Crow laws were increasingly challenged at the local level.

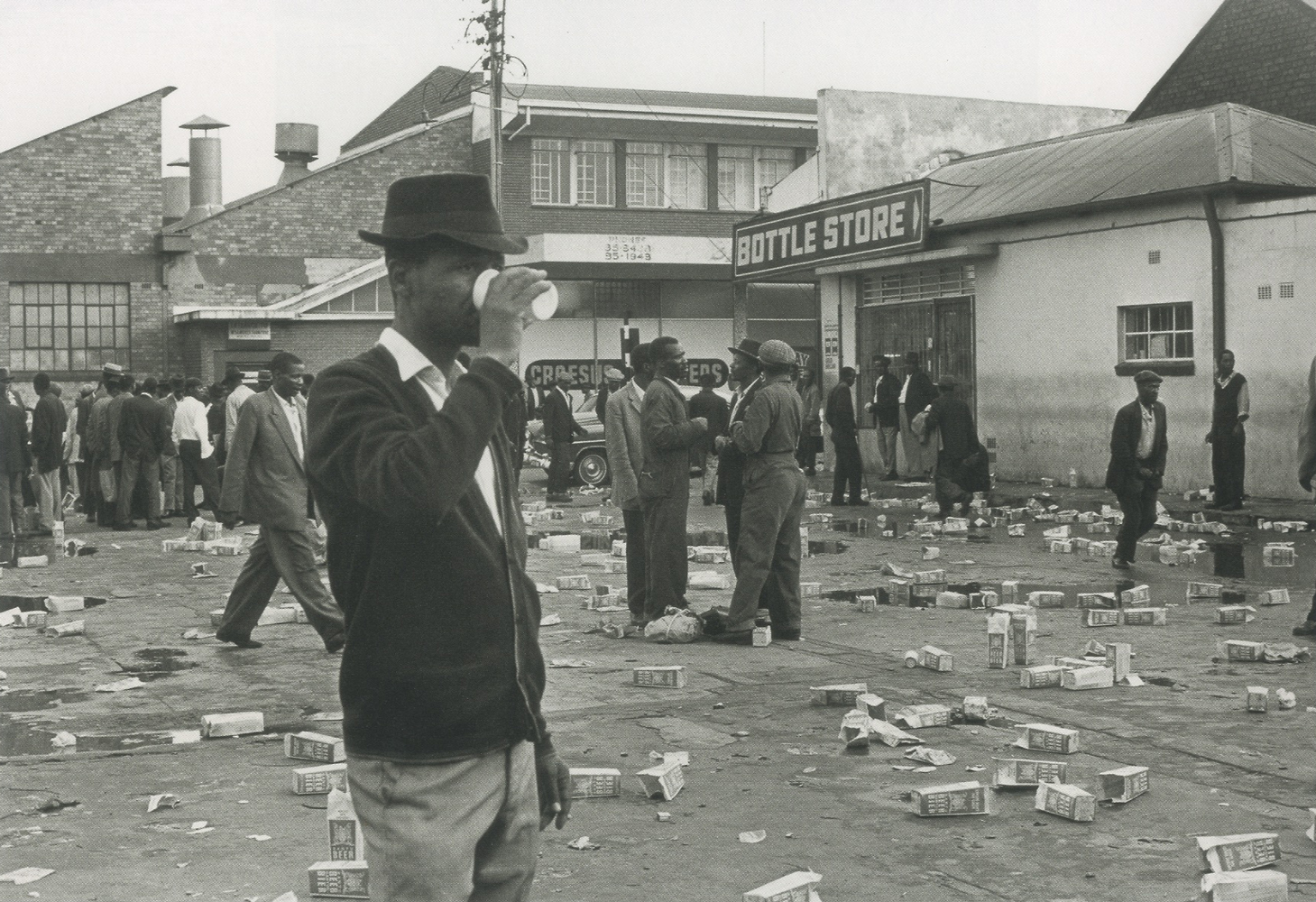

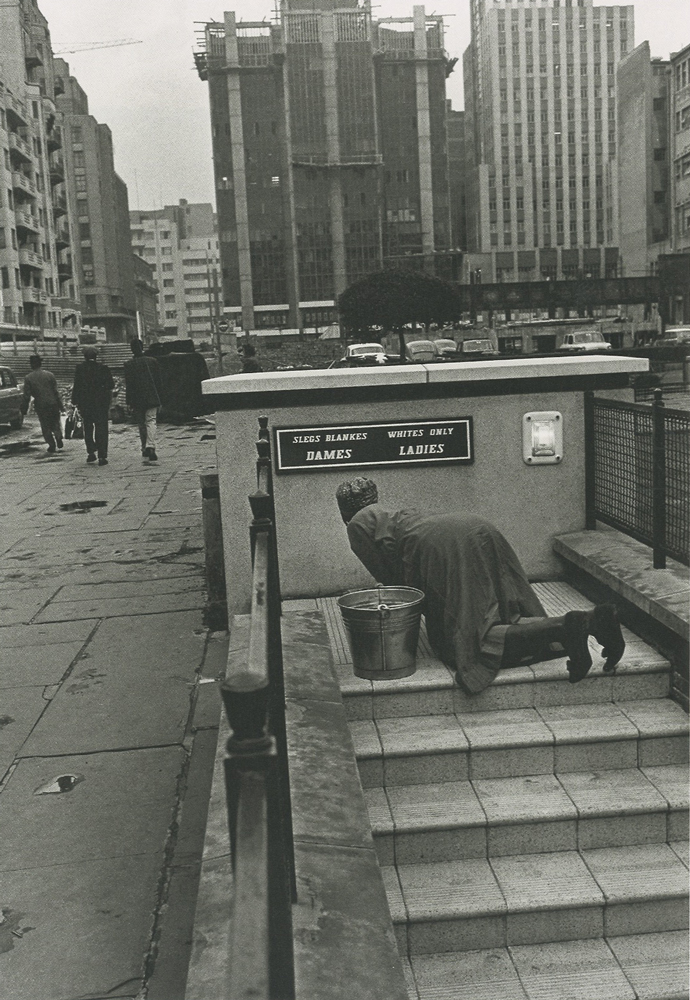

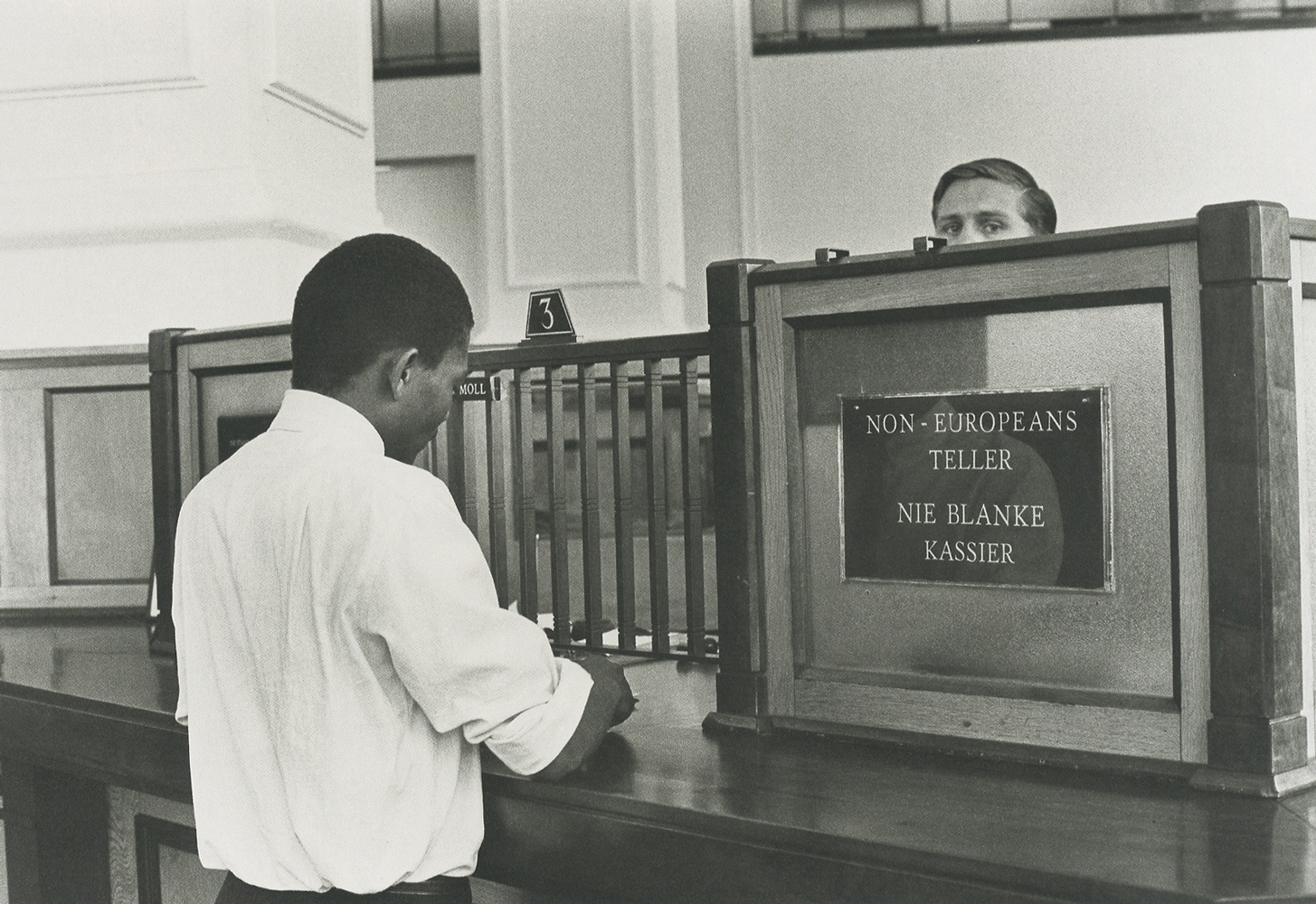

More critically, this study is intended to prove us to consider more recent wayfinding systems that perpetuate similar entitlement. In South Africa, for instance, racialized wayfinding was explicit and carefully controlled during that country’s long-standing system of apartheid. Meanwhile, in other countries, most notably in Saudi Arabia today, gender-specific wayfinding systems continue. Whether applied to hotel gyms and pools which are off-limits to women, or McDonald’s restaurants, which are restricted to women and families, the Saudi kingdom has shaped a complex system of spaces for women and aims to guide them toward it. Segregation signs not only point to separation in public space; they also serve as reminders that both law and signage are “designed” and that “designers” have a role to play in thinking critically about their purpose. We have no record of what figures like Aicher and Lynch made of the Jim Crow system; in some ways, this system might have been the underbelly of or the precursor to the universal sign age and systems that began to develop just as the segregation system was being dismantled. In modern public spaces, strangers can meet and mix in an informal manner. Traditional mores are no longer relevant and residents must be guided through unfamiliar spaces.